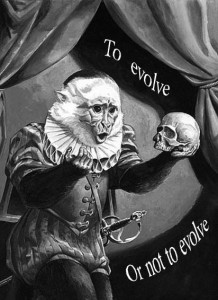

“Endless Forms,” the Charles Darwin exhibit at the Yale British Art Center, opened with two small bronze statues. In one, a squatting monkey ponders a human skull, mimicking the traditional image of the Shakespearean Hamlet wrestling with life and death. In the other, a gorilla, strong and brutish, lurches forward with a struggling sparsely clothed woman under his arm, a miniature bronze precursor of King Kong. Together, the two statues stood as emblems of the concepts of Man as ape and ape as Man. On the back wall stood the man responsible for this dualism, Charles Darwin, looking out from his portrait with quiet resolution.

The Yale British Art Center, in conjunction with the Fitzwilliam Museum of the University of Cambridge, put together a phenomenal collection of paintings, sketches, specimens and original documents from Darwin’s era. Designed to coincide with the bicentennial anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin and the 150th anniversary of the publishing of On the Origin of Species, the displayed pieces collectively spoke to the cyclic interplay between art and science.

The first room was filled with original sketches, watercolors, and engravings that represent the importance of art for science. During the early 19th century, photography was still in its infant stages, and therefore the role of dissecting, documenting, and cataloging natural specimens fell to naturalists.

The rich visual tradition Darwin grew up with was likely responsible for engendering his powers of observation. Some of the most stunning works on display were original excerpts from John Henslow’s A Catalogue of British Plants. The hand-drawn and colored botanical drawings are exquisitely crafted examples of the convergence of the artist’s hand and the scientist’s eye – sketches and watercolors which are simultaneously precise and beautiful.

The novel concept of the world as an ancient place that changes slowly over time was integral to the formulation of Darwin’s theory; and the exhibit appropriately explored how a changing scientific mindset affected the arts of the times.

Landscape paintings by Thomas Cole, William Turner and Frederic Church were displayed alongside geologic samples and fossils of marine creatures, showing how the new concept of a dynamic earth was beginning to be represented in the exposed, eroding rock faces of Hudson School paintings.

The exhibit continued on to explore Darwin’s theory of natural selection and the struggle for existence, displaying contemporaneous taxidermy pieces and paintings which speak to the new idea that each individual and group is collectively vying for survival.

At the center of the room, a stuffed hawk attacked an egret; the wings of both birds outstretched; the two species making eye contact as if in mutual understanding. It was a powerful display which evokes the radical nature of Darwin’s theories.

One wall was filled with contemporaneous images of mythical man-animals and chimeras. There was a line of paintings and etchings that looked at emotion in animals, works connected with Darwin’s lesser known publication from 1872, The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals.

Darwin wrote in this book that humans cannot express humility and love “so plainly as does a dog, when with drooping ears…wagging tail, he meets his beloved master.” Accompanying this excerpt were portraits of dogs and monkeys with furrowed brows, raised eyebrows and soft smiles, images of lesser animals that nevertheless evoke strong emotions in the viewer. The majority of the exhibit looked at the quickly blurring line between human and animal. The exhibit probed the question: if we came from apes, then are we really that different from them?

The exhibition ended with a look at how beauty was rethought due to Darwin’s ideas. Darwin theorized that the elaborate plumage of birds of paradise developed as a direct result of sexual selection by females. Darwin extended this thinking to human notions of beauty as well. There were paintings from the late ninteenth century that investigate human feminine beauty, displayed alongside beautiful stuffed specimens.

Sealing the connection between Darwin and the arts was the final room, filled with impressionistic paintings by Monet and Cezanne. Darwin’s publication dates coincided with the development of the impressionist movement in France, and the exhibit makes the argument that Darwin’s ideas concerning beauty and sexual selection “encouraged the [impressionist] idea that abstract form and color could be beautiful in themselves.”

The exhibit painted a comprehensive picture of the various ways that art and science merge and affect one another. Botanical drawings and geologic specimens were shown next to satirical etchings and famous artworks. The show was less about honoring Darwin than it was an exhibit of Darwin’s era, reflecting the interplay and exchange between art and science during a time when ideas in all cultural realms were radically changing and society was adapting to new attitudes and concepts.