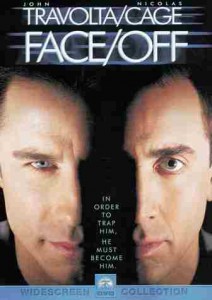

The 1997 cult classic psychological thriller Face/Off tells the story of an undercover agent who receives a face transplant in the line of duty. Though widely recognized as one of the first major references to this procedure in popular culture, the movie tells on a deeper level a story of identity, emphasizing the notion that a face is far more than a matrix of sensory organs – it is our connection to the world. In fact, our faces define so many aspects of our lives: how we are identified, how we communicate, and how we are judged. Thus, it is no surprise that with the first full face transplant just conducted in 2010, this surgery is receiving a flurry of both medical attention and ethical concern.

Once the rude suggestion of middle school bullies and quintessential subject matter of cartoons and science fiction, face transplants have recently been highlighted in modern medical dramas, from Grey’s Anatomy to Boston MD, in response to the media frenzy surrounding several recent successful transplants. This procedure is a step beyond reconstructive surgery: it consists of harvesting and grafting a donor’s face onto another person. Usually, face transplant recipients have completely lost or disfigured their faces to fire, cancer, brutal animal attacks, machinery accidents, or other unfortunate incidents. Eerie yet revolutionary, these operations have transitioned from fictional allegory to a viable treatment.

The complicated, 50-hour procedure begins when surgeons remove a donor’s face, also taking underlying fat, muscle, cartilage, nerves, and vessels. The donated face is then layered over the recipient’s skull, and the vessels, nerves, muscles, and skin are connected by advancements in a process known as microsurgical vascular anastomisis. Using a high-powered microscope and microscopic needles, surgeons stitch together the donor’s and the recipient’s homologous vessels. The exposed collagen triggers platelet and fibrinogen to aggregate, promoting healing and ligature of the two vessels. However, this surgery is not without its risks.

As with any transplant surgery, tissue rejection presents a major obstacle, but this problem is particularly concerning in the case of face transplants, as some of the tissue may be non-homologous, and the human skin is especially antigenic. Although human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing is conducted prior to the procedure to minimize mismatches, recipients will likely need to take a cocktail of several immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of their lives. Perhaps the most contributing advances in this field are these innovative immunosuppressive options, which deplete the T-cell count either directly or by interfering at various checkpoints along the proliferation pathway. For example, some of these novel sup-pressive drugs are calcineurin inhibitors, which directly block the T-cell proliferation pathway, while others act downstream, binding antagonistically to other signaling molecules, such as interleukin-2, to suppress the immune system. Additional options available today include radiation therapy, steroids, and infusion with the donor’s bone marrow. Studies have shown that these techniques eradicate the influence of HLA mismatch on the probability of rejection.

Although there is no doubt that surgical expertise and improved immunosuppressive techniques have accelerated the possibility of these transplants, the ethical concerns have been limiting to the introduction of this procedure. The recipients of face transplants may be unable to see, eat solid food, or go into public without soliciting agonizing stares, but because they are alive and capable of basic function, some believe that the transplants are morally irresponsible due to the unnecessary risk of tissue rejection, infection, illnesses, and even cancer. In addition, one wonders about the future of the field: whether face transplants will be abused for aesthetic reasons, to disguise the features of a criminal, or worse, to allow someone to assume the identity of another. Such ethical dilemmas are also seen in other transplants, such as in heart donation, in which many family members experience moral qualms about the donation, reviled at the thought of a loved one’s heart beating in a stranger’s body and at the prospect of sending someone to the grave with an empty chest. And as one can imagine, these emotional responses are only exacerbated in donating a face, an inseparable part of one’s identity.

All organ transplants are fascinating testaments to scientific advancement, but these social concerns have made face transplants especially controversial and riveting, from their first appearance in popular culture to their modern day realization.