https://chemistry.about.com/od/periodictables/ig/Printable-Periodic-Tables/Periodic-Table-Wallpaper.htm

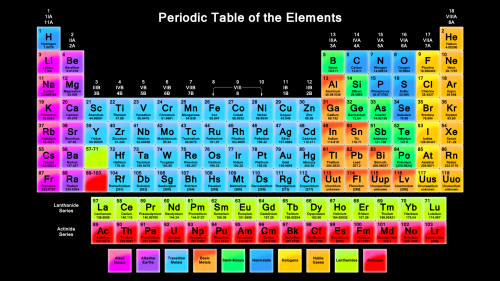

Swedish scientists have confirmed the discovery of a new element. The experiment, performed by a research team from Lund University, replicated an experiment done ten years ago by a joint Russian-American team where calcium atoms were accelerated into americium atoms to create a new element. While only two actual new atoms of the element were observed, the evidence may be enough to convince the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) to verify the discovery and add it to the official periodic table.[1]

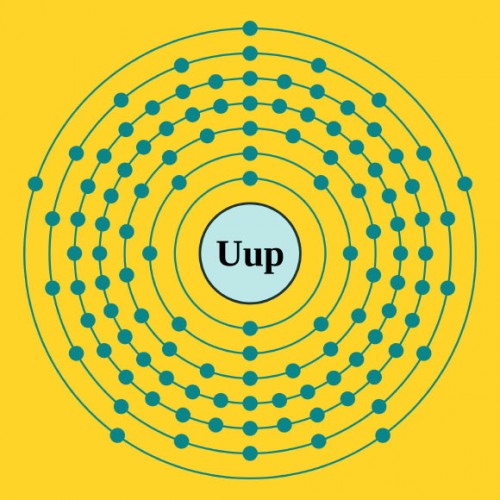

Atomic number refers to the number of protons in an atom. Atoms with atomic number higher then 92 have to be made in a lab because they are too heavy to hold themselves together and do not occur in nature. Many of those elements are created by firing elements whose atomic numbers add to the desired element’s number. For many of the collisions, the atoms did not combine properly to make a new element.[1] However, out of a large number of trials, a few collisions resulted in novel elements. In the Swedish experiment, performed at Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt, Germany, two of these successful collisions creating element 115 were observed.[2]

https://www.sci-news.com/physics/science-ununpentium-element-115-01340.html

Even so, those two nuclei did not exist intact long enough to be observed directly. The nuclear force, the force which holds nuclei together, does not act over distances as great as the width of the nucleus itself. Each proton and neutron can only bond nearby subatomic particles. This means the binding force in the nucleus grows in proportion to the number of particles in the nucleus. The problem is that the Coulomb force, also known as the electric force, can reach all the way across the nucleus so the repulsion grows much stronger as the nucleus gets bigger. The repulsive Coulomb force will overpower the attractive strong force for extremely heavy elements.[3] Because of its rapid decay, the existence of the two 115 nuclei had to be deduced from the light emitted when the atoms broke apart into smaller atoms.[1]

The report will be submitted to IUPAC. In a month’s time, if the IUPAC believes the evidence sufficient, the discovery will be credited to the original Russian-American team and that team will be given an opportunity to name the element. Currently, its provisional name is Ununpentium, signifying its atomic number of 115.[1]

https://chemistry.about.com/od/periodictables/ig/Printable-Periodic-Tables/Periodic-Table-Wallpaper.htm

When asked about the discovery, Richard Casten, Professor of Nuclear Physics at Yale, said “The reason to study this is to test quantum models to a few fermi.” (A fermi is another term for a femtometer or 10-15 meters.) Nuclear physics requires complex quantum models to make predictions. The best test of the models accuracy is to test scientist predictions at extremely high energies. At these energies the models are being tested in the most extreme situations. If they are shown to be accurate, then it can be said that the model itself is an accurate description of the world. Colliding calcium and americium at high speeds has the energy necessary to constitute one such extreme test. The experiment, Casten points out, confirms the modern model of the nucleus.[3]

Sources:

1) https://www.cnn.com/2013/08/28/world/europe/new-chemical-element/index.html

2) “Spectroscopy of Element 115 Decay Chains” Physical Review Letters 9/13/13 https://prl.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v111/i11/e112502

3) interview with Richard Casten, Yale Physics Department on 9/18/13

About the Author: George Saussy is a freshman is Morse College planning to major in physics and mathematics.