Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Have you ever wondered why some people have a strong preference for spicy foods while others can’t handle anything hotter than a bell pepper? Or why some people love the taste of coffee while others find it too bitter? Taste preferences are complex and varied, but a recent study sheds light on how our experiences, particularly when we are young, shape our gustatory cortex and ultimately influence our taste preferences.

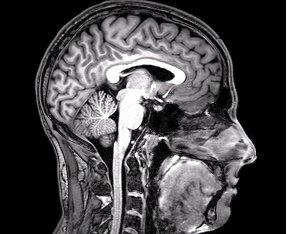

A study by neurobiology researcher Hillary Schiff and colleagues at Stony Brook University investigated how experience-dependent plasticity—the ability of the brain to change and adapt based on experience—affects the circuits in the gustatory insular cortex, a region of the brain that plays a crucial role in processing taste information.

The researchers used a mouse model and exposed infant mice to different taste stimuli over a period of several days. They found that repeated exposure to a battery of tastes led to changes in the activity of specific neurons in the gustatory insular cortex. A preference for sweet tastes was increased by eight days of exposure to four tastes, including sweet, salty, sour, and that of a nutrition shake named Ensure. Each day, mice were given one taste in their water bottle for twenty-four hours, so over eight days they received all four tastes twice.

Interestingly, the researchers found that neurons in the gustatory cortex of mice exposed to the battery of tastes were better at coding for different concentrations of sucrose. For example, exposure to these tastes led to increased activity in a specific subset of neurons called GABAergic inhibitory neurons and reduced the activity of other glutamatergic excitatory neurons.

The study examined if the preference for sweet taste is modulated by early life experience or if it can be changed by taste experience throughout life. “Windows of high sensitivity to taste experience [exist], because if we use the same paradigm in adult animals, the shift in sweet preference doesn’t happen,” said Arianna Maffei, a researcher on the study and a professor in Stony Brook’s Department of Neurobiology and Behavior.

There is plenty of untapped potential for future studies to examine the gustatory cortex. In particular, Maffei’s lab is currently interested in examining special diets, such as high-fat or high-salt diets associated with cardiovascular conditions and diabetes, and whether those diets could also affect brain development.

So what does this mean for us humans? Even for us, taste experience could have a surprisingly long-lasting effect on brain development, and thus the implications of a healthy diet in early life cannot be understated. Our taste preferences are influenced by our experiences and the resulting changes in our gustatory cortex, which plays a crucial role in processing taste information. While we can broaden our palate by exposing ourselves to new tastes and flavors, our individual taste preferences are shaped by a complex interplay of factors, including exposure to certain tastes in infancy. So the next time you try a new food and find yourself loving or hating it, remember that it’s not just your taste buds at play—your brain is adapting to the new experience.