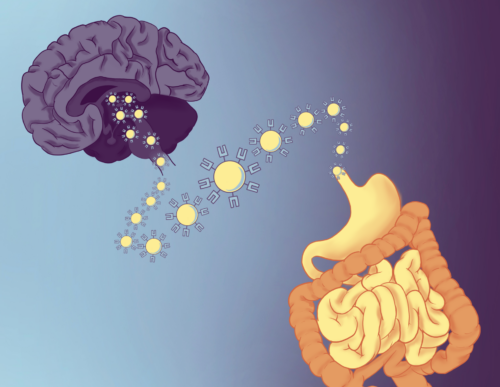

For decades, scientists have observed the intimate connection between mental health and digestive disease. Stress can trigger flare-ups of irritable bowel symptoms, and depression often coincides with gut inflammation. Yet how the immune system bridges these organs at the cellular level long remained an open question. A new paper in Nature, led by Yale rheumatologist and immunologist Andrew Wang with collaborator neurologist and immunologist David Hafler and their co-advised PhD student, Tomomi Yoshida, provides an answer. Their team reports that T cells—conventionally known as the body’s pathogen-fighting soldiers—also act as scouts that travel from the gut to the brain, carrying signals from the microbiome with them.

“This research reframes how we think about T cells,” Hafler said. “It’s not just the products of bacteria that are affecting the nervous system, but actually T cells themselves are carrying information via gamma interferons and affecting the nervous system and neurodevelopment.” In other words, instead of merely fighting infection, these immune cells integrate information from the gut environment and deliver it directly to the brain, influencing how neural circuits develop and function.

Teeing up T Cells

The story began with an unexpected clue. While comparing spinal fluid from patients with multiple sclerosis to samples from healthy controls, Hafler’s group noticed something surprising. In the control samples—taken from twelve Yale graduate students and postdoctoral researchers—roughly half of the T cells present were actively secreting gamma interferon, a signaling protein that the immune system uses to rally troops, trigger inflammation, and prime the body to fight off pathogens. By contrast, in blood, only about one percent of all T cells typically produce this protein. Follow-up studies with new samples confirmed the presence of these “inflammatory” T cells in normal brain tissue.

Mouse models revealed that T cells begin appearing in the brain at around three weeks of age, coinciding with weaning and the establishment of the gut microbiome. This timing led the team to hypothesize that the gut was seeding the brain with immune cells. To test this, Yoshida employed complementary methods to track and identify immune cells in mice. These approaches pointed to the same conclusion: T cells of gut origin were migrating into the brain.

Mapping efforts in Wang’s lab made the picture clearer: fluorescently labeled T cells were distributed across the brain but concentrated tenfold in the subfornical organ (SFO), a special region that regulates feeding and thirst and is uniquely positioned outside the blood–brain barrier. This anatomical hotspot suggested that gut-derived T cells were not random intruders, but purposeful messengers.

Special Delivery

Once inside the brain, the T cells showed themselves to be active participants in signaling. Their main product, gamma interferon, influenced astrocytes and microglia, support cells that help regulate neurons. When researchers removed the T cells, blocked their trafficking, or knocked out gamma interferon, mice developed anxiety-like feeding behaviors. The same effect appeared across multiple genetic models, strengthening the link between immune input and neural function.

To design these experiments, the team partnered with Yale neuroscientists with deep knowledge of behavioral testing. The results were modest but consistent: without T cell signals, mice hesitated to eat in novel environments, a well-validated measure of anxiety. This showed that immune input was not just present, but actually required for normal feeding behavior.

Wang likened the system to a postal system. “[Metabolites from gut bacteria] dump out […] into the blood where they can go wherever blood flow goes,” Wang said. Along the way, they can be diluted, broken down, or misdirected. T cells, by contrast, act like secure couriers. They can integrate complex information from the gut environment and deliver it directly to the brain with precision to trigger a precise functional response.

The findings challenge a central dogma of neuroscience: that healthy brains are largely devoid of immune cells. Pieces of evidence challenging this assumption had been found decades ago in chickens and rats, but were largely overlooked. “We knew that we had to provide a strong case to change these current views,” Yoshida said. By combining whole-brain mapping in mice with molecular sequencing and validation in human tissue, the Yale team assembled evidence too strong to dismiss. As Wang explained, the density and location of T cells in the brain should be viewed as a structural feature, not an anomaly. Hafler reflected that this represents a broader design principle in biology: nature often repurposes existing systems for new roles. In this case, T cells serve not only as defenders against pathogens but also as couriers of metabolic and microbial information.

The team emphasized that the study is about physiology, not clinical therapies. Yet the implications are wide-ranging. If T cells normally traffic between the gut and the brain, then misrouting or mis-signaling could play roles in conditions from irritable bowel syndrome to depression—and perhaps even Parkinson’s disease, which some suspect begins in the gut.

Open Questions

While the study presents a convincing argument for the dual role of T cells, it also opens up a host of new questions. Chief among them is the question of why T cells cluster in the SFO. The SFO’s unique position outside the blood–brain barrier gives it exposure to circulating hormones and metabolites, but why immune cells congregate in this location remains unclear. Additionally, the molecular mechanisms by which these brain-resident T cells interface with the gut remain a mystery. Their receptors may bind antigens derived from the gut microbiome, but cross-reactivity with brain-specific molecules is also possible. To investigate this, Hafler’s team is sequencing T cell receptors from the SFO to identify their antigenic targets—a step that could clarify whether the immune system is reading microbial signals, neuronal cues, or some combination of both.

The mechanism of the gamma interferon is equally enigmatic. The protein clearly influences cells in the brain, but its exact function remains to be determined. Developmental timing also raises an important question: gut-brain messenger T cells appear when mammals start feeding, but what happens at other stages of life? Do their numbers wane with aging, perhaps contributing to the risk of neurodegenerative disease?

“The next step is atlasing,” Wang said. Using mice as “wayfinders” for human studies, his group aims to map where T cells reside across different brain regions, life stages, and disease conditions. Such an atlas, he explained, could reveal whether conditions like Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or depression correspond to shifts in T cell density or placement in particular brain circuits.

Going with the Gut

The Yale team’s discovery cements immune cells as active messengers in one of biology’s most elusive relationships: the gut–brain axis. For years, this axis has been framed largely in terms of chemical metabolites produced by microbes. The new study suggests that the body has a second, more precise communication channel—one where living T cells act as couriers, integrating signals from the gut and delivering them directly to neural hubs.

“To me, what makes the paper really interesting […] is it’s not about disease, [it’s about] how the body works,” Hafler said. The importance of his team’s result lies in how fundamentally it shifts our understanding of the brain and immune system. Gut-brain immune traffic is not just a pathological feature of multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease; it is a baseline system that can be co-opted, disrupted, or exaggerated in illness.

For gastroenterologists, this work suggests that immune regulation in the intestine may feed directly into neural circuits. For neuroscientists, it reframes the brain as a semi-permeable immune environment rather than an isolated sanctuary. And for immunologists, it extends the role of T cells beyond pathogen defense into the realm of systemic communication. By working at the intersection of all these fields, the research team has managed to unravel old assumptions and uncover intimate links between systems that were once thought to be disconnected. Now, their future investigations promise to deepen and systemize this understanding, unlocking a new pathway of connection between mind and body.