Inside every cell, our DNA holds the instructions for life. To build proteins, cells first create a preliminary RNA copy of a gene. Like boarding a ship, only certain segments get “tickets” for gene expression. During a precise editing process called splicing, introns, the non-coding sequences, are removed. The remaining coding segments, called exons, are allowed on board and stitched together into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA then travels to the cell’s cytoplasm to guide protein assembly. During the process of translation, the mRNA provides instructions to build proteins.

This process usually ensures that only exons form the final blueprint, boarding the ship. However, new research shows that a specific genetic mutation can sabotage this system, allowing a harmful intronic segment to sneak on board the mRNA. This “stowaway” can produce toxic proteins that lead to neurodegenerative diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

A recent study in Nature Neuroscience from researchers at Yale School of Medicine, led by Suzhou Yang (MED ’25) and Junjie Guo, reveals how this hijacking occurs. By investigating how these stowaways access mRNA translation, they have solved a key mystery surrounding a common cause of both ALS and FTD.

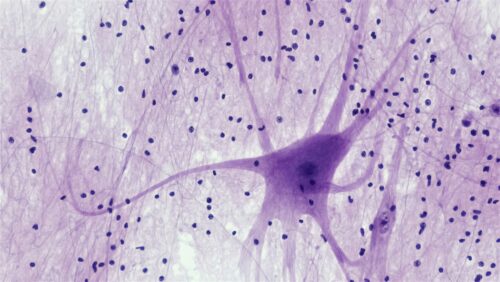

ALS/FTD are degenerative nervous system diseases, meaning they attack the nervous system progressively. ALS destroys the motor neurons that control muscles, leading to weakness, paralysis, and eventually fatal respiratory failure. FTD erodes neurons in brain regions governing personality and behavior, causing profound changes in a person’s character and ability to communicate. As the disease progresses, patients have a lower quality of life as they struggle with everyday tasks and simple movements.

A significant number of these cases are linked to a mutation in the C9orf72 gene called a nucleotide repeat expansion (NRE). While healthy individuals have fewer than thirty repeats, affected patients can carry hundreds. Although located within an intron, the NRE bypasses typical gene splicing and sneaks into the completed gene. Once translated, the hijacked gene produces toxic dipeptide repeat proteins (DPR) that interfere with mRNA translation, degrade organelles, and affect transport within the cell. By disrupting cell function and killing motor neurons, this mutation can cause ALS/FTD progression.

To isolate these rare, mutation-containing RNAs, the researchers developed a novel technique called NRE-capture-seq. After months of optimization, they developed a new unbiased approach for analyzing NREs, where they collect all mutation-containing RNAs. “We’re just grabbing anything that contains the NRE repeat in the cytoplasm of the cell,” Yang explained. Analysis of the patient cells showed that the repeat expansion promotes the usage of abnormal “cryptic” splicing signals.

The study discovered these signals redefined the gene’s architecture, incorporating the NRE into an extended exon within a mature mRNA. The extended length of their research allowed them to access aberrant splicing sites, allowing them to sneak on board as exons and serve as templates for producing toxic DPR proteins. Essentially, these “stowaways” didn’t have the tickets to board the gene but found hidden hatches within the ship to create toxic proteins and wreak havoc. Once created, these proteins disrupt essential cell functions, ultimately killing neurons.

Identifying the role of aberrant splicing in gene sequences opened possibilities for researchers to target the splicing sites to slow disease progression and reduce toxic DPR proteins within the cell. The team designed an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) to target these splice junctions. By binding to these specific sequences, the ASO flags the aberrant mRNA for destruction by the cell’s own machinery. “By decreasing the toxic DPR expression, we may be able to delay the disease progression,” Yang said.

Yang and Guo’s research provides a crucial clarification for how this intronic mutation causes harm, showing how it bypasses splicing machinery. For patients facing these devastating diseases, these findings offer a promising new direction for developing treatments that could halt the production of toxic proteins at their source and protect vulnerable neurons. Ultimately, these “stowaways” now provide a foundation for therapies that could slow neurodegenerative disease progression and preserve patients’ quality of life.