Almost all star systems are out of kilter. Take our Solar System, for example. All the planets from fiery Mercury out to distant Neptune orbit in roughly the same direction around the Sun. But the Sun is spinning too, and its spin axis is offset by just over seven degrees from the planets’ orbital plane. This angular difference between the rotation axes of the star and planets, called stellar obliquity, was previously thought to result from a myriad of chaotic influences. The environments in which planets form are something like a cosmic pool table: violent collisions with rogue objects, gravitational tugs from binary companion stars, and other dynamical processes can cause planets to twist, turn, and tilt off course. However, while some planetary orbits shift after billions of years of exotic interactions, astronomers recently discovered that other systems are born misaligned. The researchers’ result upends decades of established theory and tilts our most foundational understanding of how planets are formed.

The discovery was made by Lauren Biddle, then a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, who found that as many as a third of all planetary systems may form with an innate stellar misalignment. To reach this conclusion, Biddle and her team analyzed the largest quantity of primordial obliquity data ever collated—a feat made possible by the recent release of direct measurements from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. The data revealed that a significant number of these young systems were already misaligned, offering new insight that could rewrite the story of planetary formation.

“My journey into astrophysics has been motivated by my desire to know how the universe works,” Biddle said. For exoplanet astrophysicists like her, observing distant planets is a chance to peer into the history of our universe, uncovering how star systems behaved when they were young. By searching for patterns in planetary systems that are just beginning to form, researchers hope to explain the ancient dynamical processes that shaped our modern night sky. Stellar obliquity is an important part of this picture. The present relationship between planets and their stars is evidence for past cosmic processes that shaped their formation—processes which our own Solar System may have undergone eons ago.

Angular Anomalies

At the most fundamental level, all of these processes are mediated by gravity. Nobody needs to be convinced of how important gravity is—the name itself is synonymous with heaviness and profundity. However, gravity is hard to appreciate on the smallest scales. Two apples on a desk are attracted to one another with only a few piconewtons of force, or about one trillionth of a pound. But zoom out to the levels of moons, planets, stars, and galaxies, and gravity becomes much stronger. We feel enough attraction to the Earth to keep us from jumping more than a few feet off the ground, and the faraway gravitational tug of the moon can generate enormous tides. Zoom out further, and gravity becomes oppressive. Assemble enough mass in one place, and you get a black hole—a region of spacetime with gravity so strong that not even light itself can escape.

So what keeps the objects of our night sky from falling into each other? Why doesn’t gravity win? The answer is surprisingly simple: spin. The moon orbits the Earth, which orbits the Sun, which orbits the center of our Milky Way, which in turn is hypothesized to orbit the center of an enormous cluster of galaxies. Objects in motion stay in motion, so objects in orbit will continue to orbit, unless acted on by an outside force. The strength of two objects’ rotation is called angular momentum, and Newton’s Second Law tells us that for a system mediated by gravity, the amount of angular momentum will always stay the same.

For young star systems, this means that the enormous protostellar clouds of gas and dust from which they form begin with a fixed amount of angular momentum, which should be preserved unless the system is subject to outside forces. Therefore, when the systems develop into stars and planets, these objects should retain their initial direction of rotation; both the stars’ spin axes and the planets’ orbital planes should line up with the original rotation of the gas cloud. In the case that external influences do alter their behavior, these effects might temporarily knock the system out of alignment. But over time, internal gravitational interactions and collisions between planets should average out, realigning the spin axes of the star and orbital plane and restoring the average angular momentum. But we know that many star systems are misaligned, including some primordial systems that have yet to fully form. This implies that there are unexpected initial conditions that influence their orbits during their creation. Biddle’s study helped determine whether these orbital anomalies were prevalent enough to warrant further explanation. “We saw something special, which was when we realized that we needed to pursue this more seriously,” said Quang Tran, a Yale postdoctoral researcher on the study.

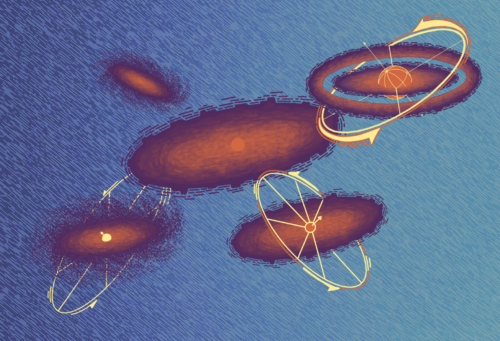

But pursuing the question was far from straightforward. Primordial stellar obliquities are notoriously difficult to measure. In an ideal case, astronomers would directly find the true three-dimensional angle between a star’s rotational axis and the face of the orbital plane of its planets by tracking their motions over time, but this would require observational evidence that cannot always be obtained. Instead, Biddle’s team turned to a proxy: the relative orientations of the star’s spin axis and the protoplanetary disk, the spinning ring of dust and debris that encircles a newborn star. Because planets form out of this disk, its tilt relative to the star’s spin axis provides a reliable indication of the system’s alignment.

Born this Way

Another challenge is gathering a sufficient number of accurate physical observations. This was almost impossible until the recent ALMA survey was released. ALMA’s array of sixty-six radio telescopes can image young protoplanetary disks in exquisite detail, allowing astronomers to measure their inclinations. Inclination is the angle at which the disk is tilted away from the line of sight of the telescope, and ALMA enables a measurement of this angle with a precision of less than one degree for many systems.

Biddle’s team was the first to incorporate this new data into their analysis. “We were at a point where we could make meaningful statistical arguments,” Biddle said. By comparing the inclination of the star to the inclination of the disk, the researchers could calculate the minimum value for stellar obliquity. These sharper astronomical observations made it possible to place stronger constraints on the obliquity calculations. After parsing through survey data alongside measurements from public archives, the group obtained star-disk obliquity calculations for forty-nine systems—a dramatic increase compared to previous studies, which had examined no more than about ten systems. According to Tran, the data-sorting process wasn’t easy. “There are a lot of ways to obtain the specific parameters of systems that we care about. It takes, I think, an attentive eye and careful consideration to make sure that what we’re doing is correct and reproducible.” Tran said. For Biddle, the daunting task of selecting appropriate observations became an opportunity to delve deeper into the rich literature of her subject. After checking and double-checking evidence from different sources, the team could confidently confirm that the results were as unexpected as they initially appeared.

The team’s most exciting moment was when tangible meaning emerged from the numbers, and preliminary data analyses revealed a clear visual trend of misalignments. “One third [of systems] is large enough that you can’t just statistically explain it with noise or randomness,” Tran said. It was then that the group realized that their discovery could lead to a new planetary paradigm. “There’s a much larger diversity of primordial environments than we originally believed, which really speaks to the diversity of exoplanets that we actually see in the universe,” Tran said. For astronomers, establishing the astrophysical trend is only the beginning. Now that Biddle and her colleagues have shown that the results are statistically significant, the next challenge is to understand why these misalignments occur in the first place.

New Twists

The team’s immediate goal is to fill in the observational gaps across different regions of space that have not yet been observed. So far, the data for this project were sourced from systems in which the planets are orbiting at distances greater than ten times the distance from the Earth to the Sun. “We need to fill in the blanks across space and time,” Biddle said. She and Tran hope that by mapping stellar obliquity at different distances and ages, they can pin down a trend in the obliquity distribution over time and explain the evolution of the misalignment that they observe. This may become possible with the future release of even more accurate measurements from the European Space Agency’s Gaia astrometric survey, scheduled for 2026.

For now, the results point to a new explanation for the small but statistically significant stellar misalignment of our own Solar System. It is possible that the misalignment observed could be primordial, just like the misalignments observed in the study. If true, this paints a completely new picture of our Solar System’s history, although much remains to be explored. As technology continues to push the limits of what can be explored, physicists like Biddle and Tran will be ready to delve into the data and make meaning of these astrophysical anomalies. Tran said, “We were just all really excited about understanding and asking those hard questions. I think that inner fire is what drives a lot of this science.”