In the face of natural disasters, deaths, and other uncontrollable events, people have searched for greater meaning in the obstacles, sometimes choosing to view misfortune punishment by a greater power or a means to teach a lesson. The converse is also true, where good luck appears as a reward for good behavior. At first glance, these thought patterns may initially appear to be a straightforward consequence of religious teachings. However, a recent study by Konika Banerjee, a graduate student conducting developmental psychology research under Yale Professor of Psychology and Cognitive Science Paul Bloom, suggests that the origins of such thinking may be found in childhood regardless of religious background.

In a previous study, Banerjee and Bloom found that while people who believed in God had a greater inclination to perceive purpose in life events, also known as holding teleological beliefs, such perceptions were also shared to an extent among non-believers. With these findings in mind, Banerjee decided to test to whether teleological beliefs emerged in young children even before they have had extensive exposure to religion. “We decided to explore the hypothesis that seeing purpose in life events may be a consequence of more general social-cognitive biases that humans possess. In particular, it may be a result of humans’ hypersensitivity to other people’s psychological mental states in the context of our interpersonal relationships,” said Banerjee. By studying children, she hoped to see whether humans naturally have a preference for purpose-based explanations beginning early in life or rather develop such preferences over time through cultural learning.

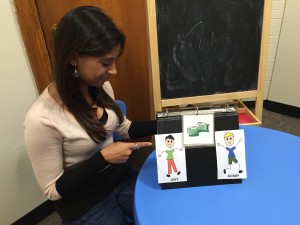

The researchers tested their hypothesis in experiments where participants of different ages were allowed to choose between teleological and nonteleological causes for descriptions of events. The scenarios described were designed to have significance to children, such as leaving a teddy bear behind. Banerjee found that young children endorsed teleological explanations for events at a significantly higher rate than older children and adults. Five to seven year olds also were likely to support irrelevant teleological explanations, such as the explanation that a character’s bike was broken in order to teach him a lesson about brushing his teeth. Older children and adults were more likely to reject irrelevant explanations. Banerjee suggested that as children grow older, they may grow more discerning and only endorse relevant teleological explanations for a life event. They may also favor teleological explanations for a narrower range of events.

These findings could change the way we understand our willingness to accept teleological explanations. Some current theories suggest that children attribute purpose to natural objects and animals because they draw parallels between these entities and human-made artifacts, which they understand as having intended purposes. Banerjee’s research supports a different hypothesis, that a more general sensitivity to design and purpose in the world encourages children to infer purpose across a variety of domains, including nature and life events. Preference for teleological explanations could also have implications in understanding the formation of belief systems and humans’ receptivity to concepts like fate and karma. “One of the questions we are hoping to pursue next with children is whether or not believing that life events have deeper purposes also entails the belief that there therefore must be some responsible agent or being who imbued that life event with a deeper purpose,” said Banerjee. As researchers delve further into human psychology, they may continue to find how our natural inclinations form the seeds for many beliefs once thought to develop later in life.