The ability to breathe through one’s nose uninhibited is really only appreciated when dealing with severe congestion. Whether in the form of the over-the-counter saline or prescription steroids, nasal sprays can bring sweet relief to stuffy noses. These common sprays function by affecting either the nasal passageway or the blood vessels directly lining it. But what if a nasal spray contained medicine that was able to reach the brain? And what if that medicine could protect against the devastating after-effects of a normally debilitating condition, like a stroke? Recently, major steps have been made towards accomplishing these feats. A research project headed by Priti Kumar, an Associate Professor of Infectious Diseases in the Yale School of Medicine, is working on such a challenge.

A stroke, or a cerebral ischemia, occurs when a clot or damage cuts off blood flow to an area of the brain. Once the neurons, or brain cells, are deprived of oxygen, they begin to die, and certain functions of the brain follow. The scientists determined that apoptosis, the normal process of programmed cell death which keeps our body at equilibrium, is one of the key factors in the unabated destruction of neurons a stroke can cause.

The researchers also developed a nasal spray which delivers a drug to block a protein involved in apoptosis after a stroke. The drug, deemed a “Fas-blocking peptide” (FBP), works to block interactions between the Fas protein and a signaling receptor in the brain. The Fas protein is essential in apoptosis, so by blocking this signaling pathway imperative in marking cells for termination after a stroke, much of the normally permanent damage can be taken out of the picture.

The FBP medicine was determined to have a massively beneficial effect after just one round of treatment through an intranasal approach. However, it is important to recognize that this isn’t the first study on intranasal treatment for ischemia. The current FDA-approved method for intranasal treatment of ischemia works by an entirely different mechanism, is predicated by getting treatment four hours from stroke onset, and not even 5% of qualifying patients receive the medication. Another nasal spray drug for the prevention of strokes, which used a different mechanism, made it to clinical trial, but was largely unsuccessful. Still, the researchers believe their FBP-nasal spray holds promise in preventing stroke-induced brain damage.

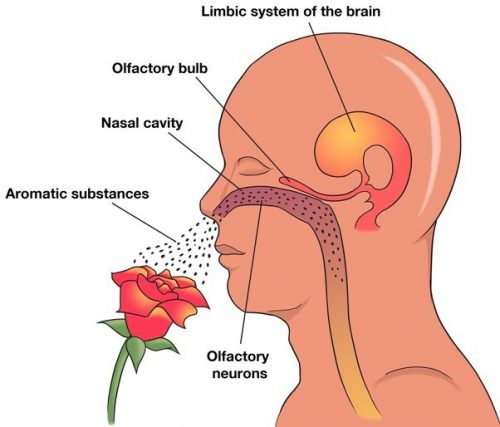

One of the key reasons so much effort has been put into intranasal delivery is the difficulty of passing through the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier is a selectively permeable membrane which blocks many pharmacological agents from passing through, essentially eliminating the intravenous approach for delivering drugs to the brain. Dr. Kumar likened the central nervous system, which includes both the brain and spinal cord, to “one of the black boxes of the human body,” describing how difficult it is to reach with medication. With intranasal delivery, drugs take the olfactory nerve pathway directly to the brain, eliminating both a majority of the travel time and the obstacle of the blood-brain barrier’s selectivity. Use of the olfactory nerves in this drug’s delivery offer an easier path to the brain. “The nose is the only area in the whole body where neurons directly come into contact with the environment,” said Dr. Kumar, explaining how patients need simply inhale for the medicine to take effect.

Dr. Kumar was also emphasized why the idea of preventing neuronal death is so important. “Unlike other cells in the rest of the body like hepatocytes (liver cells) or skin cells that can continuously divide… once [neurons] are destroyed they are gone forever.” The fact that neuronal death both occurs rapidly after stroke and is permanent is one of the biggest motivators for creating a drug that doesn’t depend on quick delivery after a stroke occurs.

The journal publication asserts that this method is both non-invasive and cost effective; Dr. Kumar also spoke about the possibilities for convenience that an intranasal drug delivery system opens. Once the drug delivery device becomes readily accessible, the intranasal approach unlocks the possibility of a future where patients could administer this medicine at home, without the supervision of medical personnel.

Although still a work in progress, Dr. Kumar’s research is very promising. A stroke is usually thought of as permanent, but that idea may be changing before our eyes. Not only could the FBP medication save many lives, it could eventually be administered in the same way that someone would clear their stuffy nose: the humble nasal spray.