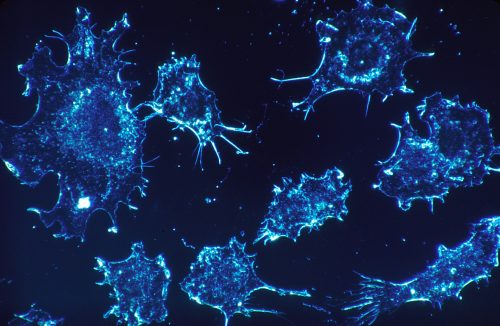

The human immune system is an arsenal ready to fend off invading pathogens. In recent years, the emerging field of cancer immunotherapy has shown that the immune system can sometimes also fight cancer.

Now Yale scientists headed by Sidi Chen, assistant professor of genetics have discovered what could be an entirely new type of cancer immunotherapy. His lab found a previously unknown immune system regulatory gene, DHX37, which suppresses the activity of CD8-T cells, the white blood cells involved in killing malignant cells.

One of the most common types of immunotherapy is based on inhibiting the protein coded by a gene called PD1. PD1 can suppress T cells, preventing them from attacking the cancerous tumor. Drugs that block PD1 and a related protein CTLA-4 have been a major part of cancer immunotherapy. However, although this treatment is highly effective when patients respond, the response rate among patients is low. In the cancers in which the treatment has been most successful, melanoma and lung cancer, only thirty to forty percent of patients respond. In other types of cancer, the response rate is usually below twenty percent.

According to Lupeng Ye, a postdoctoral associate in Chen’s lab and co-author of the latest paper in the journal Cell, it is rather common for patients to respond differently to different types of immunotherapy treatments. Just because a patient doesn’t respond to one doesn’t mean they won’t respond to any. This is what motivated their lab to study what other genes could be possible targets for cancer immunotherapy, beyond PD1 and other already known genes.

Chen’s Lab used CRISPR, a genetic

editing technique, to identify potential immunotherapy targets. These tests

were performed in mice infected with triple-negative breast cancer. Some of the

results were expected, genes like PD1 appeared. However, DHX37 was also

identified as a gene that suppress CD8-T cell activity. This gene was

previously not known to be a T cell target. The lab pursued this new

information, further investigating DHX37. In vivo experimentation found that

when the gene was targeted, the antitumor effects of the CD8-T cells were

greater than in the control. The T cells were successfully able to affect tumor

growth in mice through manipulation of the gene.

The lab then pursued preliminary studies of DHX37 in humans. The gene was found to be expressed in most organs, which is promising for its potential to treat a wide array of cancers. There was a higher level of DHX37 expression in exhausted T cells which is consistent with the idea that it is a T cell suppression gene. When the lab tested to see if high DHX37 is linked to breast cancer outcomes, they found that high DHX37 expression negates the benefit that normally comes from a high T lymphocyte score. These preliminary results in humans suggest that this research has clinical promise.

Moving forward, the Chen lab is considering how these results could translate into a therapy. They are also continuing to look at DHX37 in different tumor models that test different types of cancer and also looking at other target genes. Although the research is still in early stages, DHX37 manipulation could one day become another weapon to bolster the existing firepower of the human immune system.