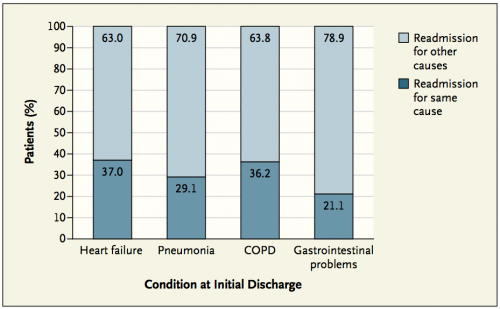

Nearly one-fifth of Medicare patients discharged from a hospital (2.6 million seniors in total) develop other medical problems within the subsequent 30 days that necessitates additional hospitalizations – many of which are unrelated to the initial diagnoses.

Professor Harlan Krumholz and colleagues examined this staggering statistic in an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Professor Krumholz is a cardiologist and the Harold H. Hines Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology and Public Health at the Yale University School of Medicine.

While interested in a wide range of medical issues, Professor Krumholz was drawn to cardiovascular disease because of its far-reaching effect on the population. Professor Krumholz explains that as a cardiologist, “you can help patients navigate through difficult periods of their life when there is a crisis. You have the opportunity to work with people who have chronic cardiovascular disease […] and help them manage it in the long term. You also have a chance to play a role in preventing cardiovascular disease to the point that the whole risk of the population decreases.”

Professor Krumholz and his group initially focused on the hospital admissions rate of patients with cardiovascular disease. But after looking at what was happening to patients after their release from the hospital, they began to see something unexpected. The observed phenomenon became what Professor Krumholz dubbed the “post-hospital syndrome.”

The posthospital syndrome is a 30-day period of vulnerability following a patient’s release from the hospital. During this period, patients are not only still recovering from their illness, but are also experiencing a period of generalized risk for a number of adverse medical events.

This period of risk is a result of cumulative stressors on patients during hospitalization that can increase their susceptibility to adverse health events. Numerous stress factors in addition to the illness include sleep deprivation, malnutrition, pain, cognitive and psychological pressures, and financial burdens. Abnormal sleep cycles and the disruption of normal circadian rhythms can negatively affect the patient’s metabolic function, cognitive performance, physical condition, and immune defenses. The combination of behavioral and physiological stresses can increase occurrences of dysphoric mood, lower physical function, and impair cognitive function.

Nutrition is also a concern: one-fifth of hospitalized patients 65 years of age or older intake less than 50 percent of the nutrients recommended to maintain their energy requirements. Malnutrition can lead to an array of medical issues including impairment of wound healing, increased risk of infections, and reduced system function.

Patients suffering from pain can experience sleep deprivation, abnormal moods, impaired cognitive performance, and lower immune functions. Pain medications can further affect cognitive function.

Cognitive stresses like the erratic and unpredictable schedules of hospitals as well as information overload can also affect patients. Many patients go home with cognitive impairment that can improve over time – but that can be profound at discharge. It is no surprise then, Professor Krumholz remarks, that “when we try to teach [patients] about their medication, habits, and behaviors […] they don’t seem to understand or listen to us.”

Instead of trying to load patients with an abundance of information, Professor Krumholz suggests that hospitals and doctors change their approach. “In the midst of trying to treat patients for a life-threatening illness, sometimes we lose sight of the smaller disruptions that can, as an aggregate, produce a lot of stress on the patient and have important consequences,” he says. Hospital administrators and doctors must work together to address this problem and to recognize all of the challenges and risks patients face after being released, and not just the initial diagnosis.

Professor Krumholz recommends teaching patients about post-hospital syndrome and taking the time to warn them about the implications of the associated mental and physical impairment. Patients should be encouraged to find someone else to help them with post-discharge instructions, to resume daily activities, and to be safe by recognizing their risk for falls and accidents. At the same time, further research is needed to characterize this period of generalized high risk. As the medical community becomes more aware of this syndrome, potential strategies are being discussed to create test programs that will improve the patient experience in hospitals as well as smooth their path to recovery when they go home.

In reflecting on his choice of cardiology, Professor Krumholz remarks, “[My area of study has] allowed me to work with healthy people to keep them healthy and with people who are acutely ill and facing life-threatening illness. It has allowed me to become involved in a field with both great public implications and great clinical implications.”

As the response to the post-hospital syndrome grows, the medical community hopes to minimize the number of avoidable readmissions.