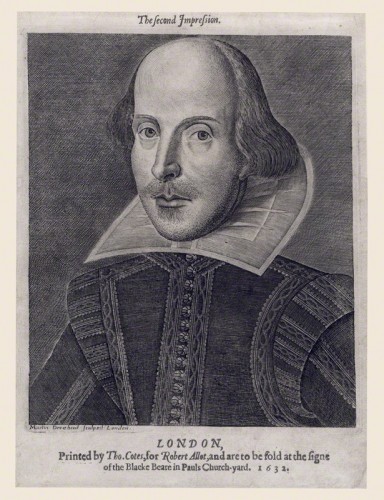

Art historians would like to think that they know what Shakespeare looked like. There are only two verified images of the great poet: an engraving published in his First Folio and a bust from his birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon. But when historians examine the “Cobbe portrait,” a painting of an unidentified man that some claim to be the Bard of Avon, they wonder if his sharp chin, long nose, and high cheekbones could truly belong to the renowned playwright. The unconfirmed portraits of Shakespeare are just one piece of a historical puzzle from which science is lifting the curtain.

In 2012, electrical engineer Amit Roy-Chowdhury teamed up with art historian Conrad Rudolph to develop a software that can objectively pick out similarities between portraits’ facial features. Roy-Chowdhury, a professor at the University of California, Riverside, brings to the stage a background in image and video analysis. Having used these techniques in biomedical imaging, multimedia, homeland security, and a variety of other projects, Roy-Chowdhury is now applying this background to art. The result is a method that can determine whether two portraits portray the same face. Using their data, Roy-Chowdhury and Rudolph hope to unravel some of history’s greatest art mysteries.

To determine whether the subjects of two portraits match, Roy-Chowdhury’s team completed an objective analysis of each portrait, noting the size and relative locations of key facial features. First, a digital mesh was applied to locate twenty-two “fiducial points” on each portrait. These fiducial points are scattered across each face and mark locations such as the corners of the eyes and mouth. Together, they enable the computer to collect data on features including the subject’s forehead, chin, eyes, ears, and mouth. By comparing these areas on two different portraits, Roy-Chowdhury was able to generate a similarity score for each pairing. The higher the similarity score, the more likely that the two portraits shared a subject. With this information, art historians and curators can decide for themselves whether the subjects in two portraits are the same.

In the July 2013 “Ultimate Tut” episode of the PBS series “Secrets of the Dead,” Roy-Chowdhury showed how this technology could be applied to determine whether one of King Tut’s death masks had actually been created for the young pharaoh, or if it had actually been designed for Tut’s step-mother, Nefertiti. He compared the fiducial points on Tut’s mask with those on a bust of Nefertiti, and concluded that the mask had likely been created for the latter. “The purpose of doing this is to come up with an objective measure and a number,” said Roy-Chowdhury to PBS. “This number cannot be obtained just by staring at those faces.”

Tut’s death mask is just one of countless instances where Roy-Chowdhury’s technology is applicable. According to a 2013 paper from his lab, other test subjects include unverified images of Sforza, Mary Queen of Scots, and Constanze Mozart.

However, even Roy-Chowdhury’s software cannot solve all of these mysteries. For social reasons, artists might have altered the appearances of their subjects, making it more difficult to determine whether a portrait match is legitimate. Portraiture is an imprecise art, dependent on medium, angle, and artist style. Therefore, Roy-Chowdhury realistically expects variations in portraits of the same figures. In his study of King Tut’s death mask, he concluded that a close to 85 percent similarity score between Tut’s mask and Nefertiti’s bust was close enough to claim that the mask was probably created for Nefertiti.

And for people like Shakespeare who may have sat for portraits multiple times throughout their lives, the technology may fail to adjust for facial changes caused by aging. As Roy-Chowdhury’s team develops its software to account for some of these problems, the lack of a large identified portrait database poses an additional challenge: While researchers were able to work with a few confirmed images of Shakespeare, they may not be as lucky with other historical figures.

Nevertheless, Roy-Chowdhury’s software offers art historians a chance to get to know some of history’s favorite characters. With hard data to aid the naked eye, they will be able to recognize Shakespeare with confidence.