“We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.”

–John F. Kennedy. September 12, 1962

In the fifty-one years since John F. Kennedy’s Rice Stadium Moon Address, space exploration has captured the imagination of many generations in the U.S. and abroad. His vision articulated goals much grander than the moon landing, especially his intention that as the “exploration of space will go ahead … we mean to lead it.” Have we fulfilled his mandate?

Space exploration now faces a changing scene, as industry and commercialization, rather than government efforts, claim a growing share of aerospace development in the U.S. Pressure from the burgeoning Chinese space development program and our recent reliance on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft to reach the International Space Station (ISS) have forced us to acknowledge a globalizing trend in space exploration. With exquisite advances in robotics and remote data sensing, the glorious manned space missions of the Apollo era now share the limelight with distant probes and unmanned rovers. Through tough budget cycles and trying tragedies, we have repeatedly postponed the challenge posed to us by President Kennedy, though the allure of space exploration has also repeatedly recaptured our attention, sparking further discovery and innovation.

NASA’s Evolving Role

Our modern conception of space exploration was born during the Cold War. The successful Soviet launch of Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, on October 4, 1957 spurred the U.S. government to create NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) and place space exploration high on the national security priority for over three decades of fervent technological competition.

Now, NASA shares the opportunity for exploration with circles beyond their core of career experts. Through their Microgravity University, space exploration pulls in young talent, giving teams of budding aeronautical engineers, astronauts, and space scientists the opportunity to solve NASA’s current design challenges. Frank Prochaska, Manager of the Reduced Gravity Education Flight Program (RGEFP), creates these opportunities for the students to “use their creativity to solve technical problems currently facing NASA engineers and scientists.”

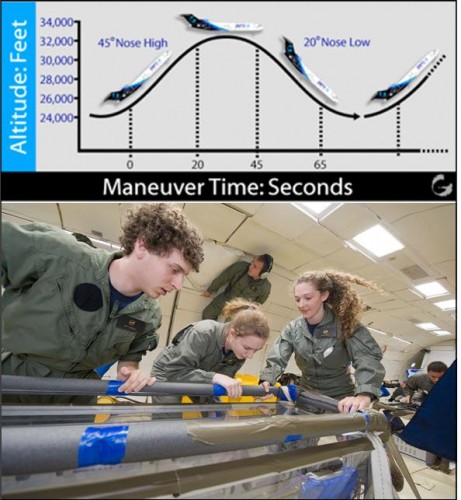

After months of technological development in collaboration with a stringent NASA oversight committee, the students fly their experiments in a modified Boeing 727 “Zero-G” aircraft over 30 physically demanding parabolas of microgravity, normal gravity, and hypergravity. Prochaska heralds these youth-centered efforts as the future of space exploration. As NASA updates its mission for the twenty-first century, we can expect new creativity in their programs, such as the RGEFP, and a revitalized reverence for man’s desire to explore.

Throughout NASA’s projects, collaborations between government technology and academic research labs stand poised to produce key discoveries in space science. Yale Professor of Astronomy Priya Natarajan looks forward to a promising future for space exploration, most recently exemplified in the breathtaking achievement of NASA’s 1977 Voyager probe as it exited the Solar System. Natarajan hopes that the probe, after years of loyal service to the scientific community, will offer captivating new insights for astrophysics. Reminding us of the scale of this achievement, and more to come, she noted that not since the intrepid explorers of the 1500s has a product of the human race crossed such a momentous frontier. For her research on the fundamental nature of gravity and dark matter, Natarajan anticipates fruitful future projects with the next generation of space probes such as LISA, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. Though NASA has had to step away from LISA due to funding challenges, the European Space Agency will take on the mantle of advanced gravity research in their plans for the New Gravitational-wave Observatory.

These symbiotic relationships between NASA technologies and academic research promise an exciting future — but is this promise enough? Can the government muster the economic capital and efficiency to get man back to the moon? Enter a new figure in this longstanding relationship: space exploration industry. Though private industry contractors have long played a part in the technology development process (notably Boeing’s long history in aerospace engineering), the last ten years have witnessed an explosion of new private space ventures and companies. From cutting-edge rocket development to commercial luxury space flight, each corporation has found its niche in the market. Now attracting top talent, these profit-centered industries are taking a competitive, time-pressured and dramatically efficient approach to space exploration.

The Rise of Space Industry

In less than a decade of existence, Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX) delivered a cargo payload to the International Space Station via their Dragon Spacecraft. As the first commercial spacecraft ever to dock with the ISS, the Dragon represents a successful collaboration with NASA through the Commercial Crew and Cargo Program. Through further innovation, the young company’s recent advances in reusable rocketry with the Falcon 9 rig will shape a new paradigm for future launches. In 2012, NASA announced agreements with three American space industry companies “to design and develop the next generation of U.S. human spaceflight capabilities, enabling a launch of astronauts from U.S. soil in the next five years.” Working under the Commercial Crew Integrated Capability initiative, Sierra Nevada Corporation, SpaceX and Boeing were collectively awarded over $1 billion to develop new technology. These companies are revolutionizing space exploration rapidly and inspiring a new generation of aerospace engineers, scientists, and space enthusiasts among the public.

Fundamental to the recent birth of the space industry, incentivized competitions run by the X PRIZE Foundation have mobilized public interest and profoundly advanced the state of our society’s space exploration ventures. As stated in their mission, X PRIZE competitions “bring about radical breakthroughs for the benefits of humanity, thereby inspiring the formation of new industries and the revitalization of markets.” Most influential for space exploration, the $10 million Ansari Prize was awarded to Burt Rutan’s SpaceShipOne team in 2004, after they succeeded in achieving private suborbital flight two times within two weeks. The Ansari Prize is often hailed as an impetus for interest and innovation in space exploration.

A more recent exploration competition began in 2007, the Google Lunar XPRIZE headed by Alexandra Hall. In order to win the $20 million prize, by December 31, 2015 a private company “must land safely on the surface of the Moon, travel 500 meters above, below, or on the Lunar surface, and send back two ‘Mooncasts’ to Earth.” One of the companies engaged in the competition, Astrobotic Technology, has already secured a contract with SpaceX for a launch on the Flacon 9 in October 2015.

Director Alexandra Hall predicted that “the future of space exploration will be one marked by partnerships of all kinds and involving disciplines that have not necessarily been involved with space until now.” Compelling economic arguments can be made for investment in space technology, as the success of commercial entities “will lead to businesses, job growth, and wealth in sectors from biology, to materials science, to mining and resource utilization.” Google’s Lunar XPRIZE aims to breach the frontier beyond Earth’s orbit repeatedly and at low cost. To achieve this, Hall prioritizes further developments in lunar orbit communications and navigation networks, the establishment of refueling depots at strategic points in space, and the expansion of communications networks on earth that receive signals from space. Commenting on the impact of the rise of space exploration industry, Hall noted that “moving the R&D from just being governments, to including the commercial sector means that everything from the amount of risk that we’re willing to take, to the legal and regulatory infrastructures will be challenged. All for the good.”

Creative new approaches to space exploration hardly end with the X PRIZE Foundation. Planetary Resources, a company dedicated to asteroid mining, has stated that “harnessing valuable minerals from a practically infinite source will provide stability on Earth, increase humanity’s prosperity, and help establish and maintain human presence in space.” With influential industry backers including Google’s Larry Page and Eric Schmidt, Virgin Galactic’s Richard Branson, X PRIZE’s Peter Diamandis, and James Cameron as well as a team equipped with technical talent, Planetary Resources is surprisingly well placed to tackle what would have been an outlandish sci-fi mission just a few years before.

Building up to their asteroid ambitions, they recently completed their successful Arkyd Kickstarter campaign, raising over $1.5 million in the first crowdsourced funding venture to offer public access to an advanced space telescope. Space exploration crowdsourcing is taking off in its own right, as the CubeSat Project, “an international collaboration of over 40 universities, high schools, and private firms developing picosatellites containing scientific, private, and government payloads” gives everyday individuals the chance to send small-scale modular projects into space. With a crowdsourced funding model, the cost is shared among all the participating members of a particular cube’s launch.

The Pressure and Promise of Globalization

Complicating this dynamic network of governmental, academic, industrial, and now crowdsourced interests within the U.S., several other nations have taken steps to pursue space exploration. China’s proposals for an International Space Station by 2020 and a Chinese moon colony soon thereafter force us to grapple with the political implications of space technology. Hall stated, “as space exploration matures, I believe we will increasingly see the role of governments and consortia of nations in building out infrastructure at each new frontier.” Prochaska concurred, noting that space exploration is a “phenomenally complicated puzzle and we’re working internationally with other Government space agencies” to put the pieces together.

These multinational efforts stand to incentive competition, galvanize space exploration, and advance humanity’s prospects for the future. As we look to the final frontier, a diverse fellowship between corporate and government interests, small-scale and large-scale projects, and research will take us there. The future of space exploration is bright and now more accessible than ever.

About the Author: Ariel Ekblaw is a senior Physics and Math-Philosophy double major in Pierson College. Currently working with Yale Professor Eric Dufresne on a biophysics soft matter project, she flew in Zero Gravity with the Yale Drop Team in 2012. She hopes to pursue a career in bioengineering for space or astrobiology.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Frank Prochaska, Priya Natarajan, and Alexandra Hall for their time and thoughtful contributions to the article.