Have you ever wondered about galaxies far, far away? If you have, then you are not alone.

An international team of scientists recently discovered hundreds of hidden, nearby galaxies while surveying the region behind the southern Milky Way. Using the Parkes radio telescope in Australia, which is equipped with an innovative receiver to detect hydrogen radio waves, the team uncovered 883 galaxies. A third of these galaxies had never been detected before. Until now, the Milky Way’s dense stars and dust have prevented scientists from mapping this region of extragalactic sky beyond our galaxy.

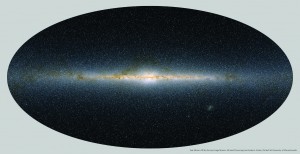

Patricia Henning, an astrophysics professor at the University of New Mexico, helped lead the project. The obscured region of extragalactic sky she surveyed is commonly called the Zone of Avoidance. “That’s a wonderful, old-fashioned name that dates back to before astronomers even knew that the spiral nebulae that we saw were actually external galaxies,” Henning remarked. “Astronomers noticed that fuzzy patches of spiral nebulae avoided this big band around the sky. Now we understand that those nebulae are actually external galaxies, and that it’s just difficult to see those galaxies in visible light through our own Milky Way.”

“The combination of many stars and obscuring dust means that the light from galaxies behind the Milky Way really can’t penetrate our galaxy and get to our optical telescopes,” Henning explained. Instead of attempting to detect light, the research team used the radio signature of hydrogen gas, which is present in many galaxies, including ours. Hydrogen gas emits a wavelength that is much longer than optical wavelengths and larger than obscuring dust. Since this wavelength easily passes through the dust of our Milky Way, Henning and other researchers could detect the hydrogen signatures from these hidden galaxies using the Parkes radio telescope.

The results of this survey technique were highly interesting to astrophysicists. By locating the galaxies, researchers could see mass concentrations associated with structures above and below the galactic plane, the region which contains most of the luminous objects in the galaxy (to visualize our galactic plane, imagine our galaxy’s disc “edge-on,” or lying on a two-dimensional plane). Some mass concentrations from the survey matched up with our previous map of the Milky Way’s planar region, but many clumps of mass were new. In particular, researchers found mass associated with many new galaxies in a famous region called the Great Attractor.

The Great Attractor has been a mystery to scientists for decades. We have known for a hundred years that galaxies move apart due to the expansion of the universe, but galaxies also have additional velocities due to gravitational motions. In regions of high galactic mass, gravity is stronger, creating motion due to gravitational perturbations between neighboring galaxies. Scientists have understood since the 1980s that galaxies feel the gravitational pull of other galaxy clusters. They associate these galactic movements with areas of high mass by comparing galactic flow fields with galaxy maps. The Great Attractor is puzzling to scientists, however, because the discovered galaxies in this region do not account for the gravitational attraction it generates. Researchers speculate that the region must contain a large amount of mass unassociated with previously discovered galaxies. “We were looking for regular galaxies that would help account for this mass,” said Henning.

Henning pioneered this project’s specific survey technique back in 1987, but until this project, it could not be put into effect because of a lack of sophisticated technology. Even when the project first began, the Parkes telescope was the only telescope with a receiver advanced enough to detect hydrogen waves. “We’ve known since the 1980s that it is plausible to do what our team has accomplished,” Henning reflected. “The receiver that’s on the Parkes Telescope was absolutely fundamental to our being able to conduct this survey.”

The team was comprised of scientists from the United States, the Netherlands, South Africa, and Australia, but collaboration was never an issue. “Like-minded and like-interested people came together to use the Parkes telescope,” Henning explained. “We collaborated sometimes via Skype. You can do international collaborations pretty easily these days.”

Henning is leading a new team in a project in Puerto Rico, using another telescope to map the Zone of Avoidance in areas north of where it was mapped using the Parkes telescope. Since this telescope is highly sensitive, researchers will be able to detect objects that are very small and farther away. Henning expects to find many more galaxies than were previously discovered in the southern Zone of Avoidance.