Fueled by trepidation of the world’s most cryptic disease—cancer—we scrutinize labels for carcinogenic substances and lather ourselves with sunscreen, while the media frequently spotlights publications claiming to have found the “cancer gene” for a particular tissue.

Cancer, however, is a complex disease, and cannot be reduced to one disruptive gene or protein. In response to the need to study cancer more holistically, the Cancer Systems Biology at Yale (CaSB @ Yale) initiative has emerged at the Systems Biology Institute on West Campus. In August 2016, the initiative received a $9.5 million grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH). Scientists taking part in the initiative are working on an extremely challenging task. They are studying two of the most aggressive types of cancer: glioblastoma multiforme, a type of brain cancer, and melanoma, a form of skin cancer.

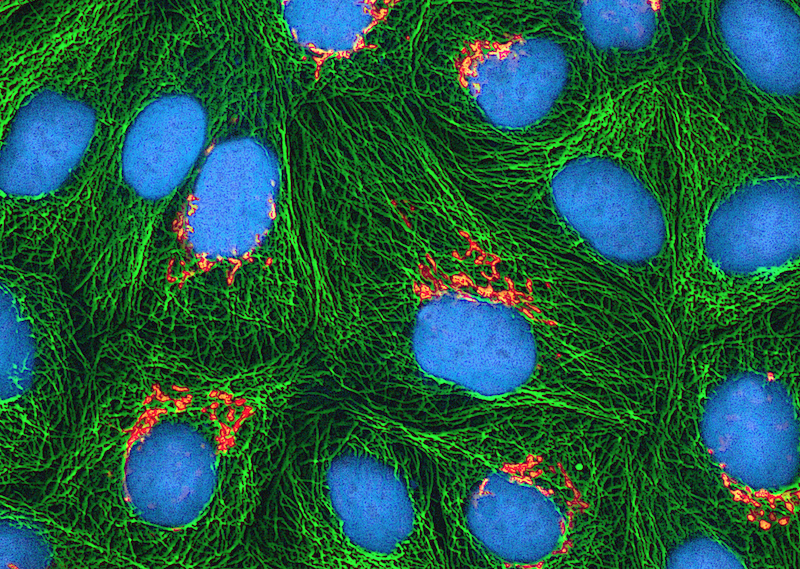

One of the foci of the initiative is phenotypic plasticity, in which cells with the same genetic code exhibit different behaviors. “We see evidence that within a tumor, cells can be in different states, producing for instance two simultaneously exiting populations—invasive migratory cells and proliferative cells— which interact resulting in a balance,” said Andre Levchenko, director of the Yale Systems Biology Institute. These cells have the potential to switch their behavior, he said, explaining that a drug that suppresses tumor growth may change the balance and encourage cells to metastasize, for instance. Systems biology is thus helpful in understanding how targeting one aspect of a cancer could have unintended consequences elsewhere in the body.

In order to establish this understanding, CaSB @ Yale has brought together experts from a wide range of disciplines. At its heart is a collaboration between the Yale Cancer Biology Institute; the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Institute for Biological, Physical and Engineering Sciences; and the Yale Cancer Center. Faculty in a wide range of departments—from genetics to mathematics to pharmacology—will engage in research through CaSB @ Yale.

According to Levchenko, the establishment of CaSB@Yale was serendipitous: the NIH initiative that is funding CaSB@Yale originated around the same time as scientists from these departments were looking for ways to collaborate. “Bringing together all these institutes seemed like puzzle pieces falling together.” Levchenko said.

By coupling an innovative, interdisciplinary approach with world-class faculty, CaSB @ Yale is poised to shed light on an even greater puzzle: the aggressive nature of some forms of cancer.