Does keeping a gun at home affect one’s mental health? Is abortion the best option for a particular situation? To what extent does smoking marijuana affect one’s life? Research published in October 2016 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science by Yale professors Matthew Goldenberg and Eitan Hersh suggests that physicians’ answers to these questions may depend on their political affiliations. In other words, answers to hard health questions depend on whom you ask.

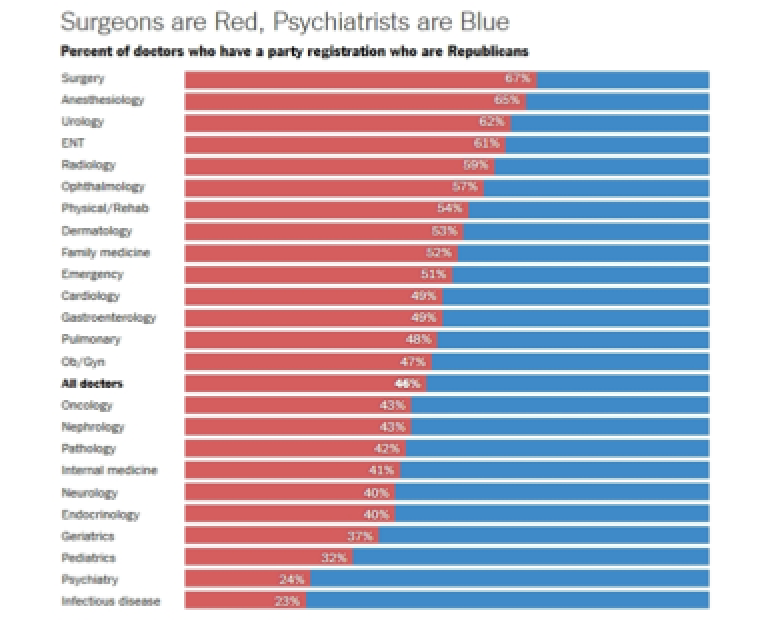

Physicians are trained to be objective thinkers, but they are only human. The Yale team’s research joins several other studies that are dismantling the notion that physicians are completely detached from biases when treating patients. Earlier in 2016, certain medical professions were found to be associated with specific political parties. “What we found in an earlier study published in The New York Times is that certain professionals, like pediatricians and psychiatrists, are more likely to be Democrats, while others like surgeons tend to lean Republican,” Goldenberg said.

Because the study only revealed a correlation between party and profession, the next step was to examine causation. The researchers first hired a data analysis company called Catalyzer to review information from sources such as the National Provider Identifier database. With these public databases, the company matched doctors with their political affiliations. However, because certain professions may be correlated with certain affiliations, the Yale researchers only chose to focus on a subset: 20,000 primary care physicians located around the United States. The Yale team then gave each primary care doctor who volunteered for the study nine vignettes describing different patients and their current circumstances. Example scenarios included a patient who used recreational marijuana three times per week and a patient who had two previous abortions but was not currently pregnant.

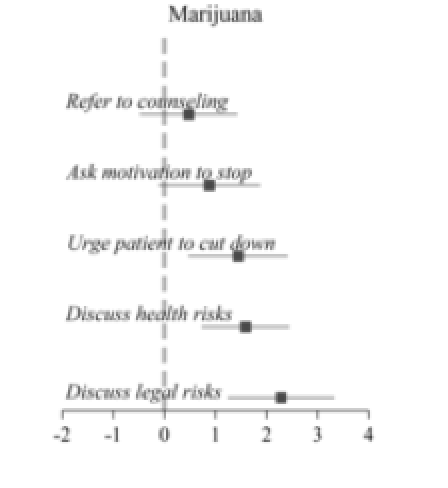

The results demonstrate that for highly politicized issues, there are indeed differences between the two groups in the treatments the physicians prescribe. “On politically salient issues, especially abortion, guns, and marijuana use, there is a difference in treatment approaches,” Goldenberg said. For example, conservative doctors were more likely to respond to the scenario involving marijuana by suggesting that they would discuss the disadvantages and alternatives to regular marijuana use with their patients. On the other hand, liberal doctors were less likely to talk to patients about recreational marijuana use, viewing it as a minor issue. As such, differences in political beliefs can translate into divergent outcomes.

At the onset, these biases suggest that patients, when faced with highly politicized medical issues, may want to reconsider their choice in physicians. That said, Goldenberg is still cautious about explicitly connecting political beliefs to treatment options. “More studies still need to be done in order to replicate the results,” he said. “As it stands now, we are not sure if different political beliefs directly translate into outcomes. Using a larger sample size would be ideal,” he added.

Further studies, including those on other politically salient issues, will need to be performed to more fully understand the political underpinnings of physician-patient interactions. For example, certain LGBTQ groups circulate “gay-friendly doctor” lists, suggesting that certain communities have faced biases in primary care.

While patients’ demographics and their effects on healthcare have been extensively documented, researchers have not yet devoted much time to studying the backgrounds of physicians themselves. Until the details manifest more clearly, patients can keep one important message in mind. “Every physician inevitably will bring certain biases into the examination room, and we should be aware of those biases,” Goldenberg said.