From space, most stars never twinkle. Some dim periodically, betraying the clocklike passage of planets. But there is one star that flickers unlike any other seen before. Known as “Tabby’s Star,” this astronomical enigma has captured the imaginations of thousands of scientists and amateurs alike. Its mysterious blinking behavior was first spotted by amateurs and subsequently was investigated by former Yale postdoctoral fellow Tabetha Boyajian ’16, now an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Louisiana State University. Because the behavior of Tabby’s Star is completely unlike that of similar stars, scientists have resorted to an array of wild theories as potential explanations—from a massive comet chain to an alien megastructure. New research suggests that the star is even more peculiar than previously thought, complicating attempts to explain its behavior and reinforcing the need for continued study of its idiosyncrasies.

Tabby’s Star (more formally known as KIC 8462852, and more colloquially as the “WTF”—Where’s The Flux?— Star), was observed from 2009 to 2013 by NASA’s Kepler Space Observatory. This orbiting telescope is designed to detect the shadows of exoplanets as they pass in front of stars. But because of its foreign behavior, Tabby’s Star was not detected automatically; it took the relatively untrained eyes of citizen scientists—amateur astronomy enthusiasts who volunteered to pore through Kepler’s data with their own eyes—to spot the bizarre signal. “When they first showed the data to me, I just thought it was bad data”, Boyajian said. “Our automated pipelines missed this feature because it was unlike anything we had seen before,” she added.

So just what is it about Tabby’s Star that is so perplexing? Most stars exhibit small, periodic, symmetrical dips in their brightness, if they exhibit observable periods of dimness at all. These dips are the result of the regular passage of an orbiting planet in between the star and the telescope, a planetary eclipse of sorts. But research by Boyajian demonstrated that Tabby’s Star exhibits frequent and irregular dips in its brightness, too large to be caused by a planet. New research led by postdoctoral researcher Benjamin Montet of the University of Chicago revealed another feature not seen in any nearby or similar stars: a dramatic, long-term dimming over the four-year course of the Kepler study.

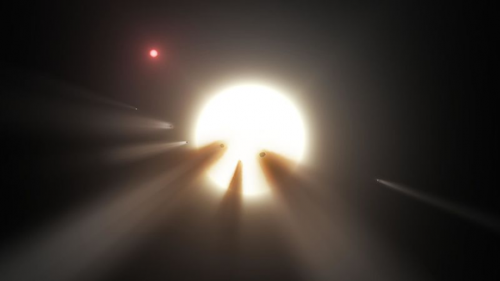

The sum of these observations leads to a troubling but fascinating dilemma: nothing like Tabby’s Star has been seen before, and no single theory can make sense of all of the star’s unique characteristics. “There is no good explanation for what’s going on,” Boyajian said. All explanations must involve an event far larger than anything of its kind seen before, or a controversial phenomenon that has been theorized but never observed. One of the favored explanations presented by Boyajian’s team consists of a comet swarm around the star that causes its fluctuations in brightness; however, all comet swarms thus observed so far are hardly a tenth of the size that would be necessary to produce such a large signal. The most well-known explanation for the star’s behavior is an energy harvesting system built by extraterrestrial life (known as a Dyson sphere or Dyson swarm). That said, any theory of such elaborate proportions, particularly one based on a phenomenon that has yet to be observed, must be regarded with suspicion.

When Kepler refocused in 2013 on a new mission, it appeared that researchers would have to rely on only four years of data to solve this astronomical Rubik’s cube. But once again, astronomy enthusiasts came to the rescue: a Kickstarter project initiated by Boyajian raised over $100,000—enough to fund a year of constant observation of the star through Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network. With continuous monitoring of Tabby’s Star at multiple wavelengths, Boyajian’s team will be able to observe long-term trends. They will also be able to react in real time to short-term changes in the star’s intensity, which wasn’t possible during the Kepler observations. Sudden changes will set off a “real-time trigger” that will cue the team to take a burst of higher resolution images, allowing them to better capture unprecedented rapid fluctuations in the star’s brightness. Subsequent analyses of these images have the potential to shed light on the cause of these fluctuations.

While conclusions regarding Tabby’s Star are pending further observation, one message has already manifested: citizen science is a force with which to be reckoned. The discovery of Tabby’s Star and its continuing observation are the result of the massive amount of support that astronomy enthusiasts can provide; in addition to the global network of professional telescopes, Tabby’s Star will be monitored by the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), an organization comprised primarily of amateurs.

There are, of course, limitations to citizen science in the realm of astronomy. AAVSO is providing observations of Tabby’s Star to Boyajian’s team, collected by the home-operated telescopes of astronomy enthusiasts. While this data may prove to be a helpful supplement, AAVSO is unable to provide a “real-time trigger” in the way that the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network can. The numerous observation stations operated by AAVSO are not entirely standardized. As a result, observations from one station are systematically offset from others, precluding the use of AAVSO to identify short-term fluctuations.

But what citizen science lacks in finesse, it makes up for in both manpower and willpower. “We were quite surprised by how many people were interested in supporting this project,” Boyajian said. Unlike many citizen scientist projects that rely on the human brain’s exceptional ability to recognize patterns in images— “pretty pictures”, as Boyajian termed it—signing up for the Kepler project guaranteed hours of staring at graphs. That didn’t stop over 300,000 citizen scientists from contributing to the project, and from being the first to spot this star’s bizarre behavior. “Not a lot of astronomers take advantage of this immense resource,” Boyajian said. “I can definitely see citizen-science like this growing in the future.”