A man asks a room full of people, “So, who here has told a lie since the beginning of this year?” Everyone sheepishly raises his or her hand. “Who generally thinks of themselves as a decent, honest person?” he asks. Everyone again raises his or her hand. “How can it be that at the same time we think of ourselves as honest, we recognize we are dishonest?”

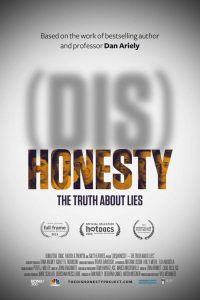

The man is Dan Ariely of Duke University, whose work in behavioral economics inspired the documentary (Dis)Honesty: The Truth About Lies. The film features clips from an interactive lecture of Ariely’s, interspersed with reenactments of his team’s experiments and personal testimonies from individuals who have faced serious consequences for lying and cheating. Their stories cover topics ranging from insider trading to adultery.

The man is Dan Ariely of Duke University, whose work in behavioral economics inspired the documentary (Dis)Honesty: The Truth About Lies. The film features clips from an interactive lecture of Ariely’s, interspersed with reenactments of his team’s experiments and personal testimonies from individuals who have faced serious consequences for lying and cheating. Their stories cover topics ranging from insider trading to adultery.

Most of reenactments show variations of what Ariely calls “the matrix experiment,” a key tool that he and other behavioral economists use to evaluate people’s levels of honesty. A notable finding from their experiments is that many “little cheaters” do more damage to society than the few “big cheaters” that make headlines for large-scale tax evasion and fraud. Small acts of dishonesty add up to major costs, such as the IRS being cheated out of 15% of its tax revenue.

Although the film is full of interesting facts and compelling stories, it lacks cohesiveness and flow. The insertion of personal anecdotes often felt choppy, almost like an afterthought designed to artificially generate emotional connection. Even maintaining the existing structure, director Yael Melamede would have done well to more obviously connect these stories to the phenomena Ariely describes in his lecture.

The film ends on a clear, hopeful note despite its sobering message. Ariely’s team found that cheating almost disappeared when they reminded participants of their own morality by having them sign an honor code or write down the Ten Commandments. Some schools have already put these findings into practice by requiring students to sign honor codes before taking exams. Because Ariely’s team also concluded that most people are dishonest to similar extents and react similarly to various situations, their findings are widely applicable and may help move us towards a more honest global society.

Rating: 3 out of 4 stars