Recently, it may seem that politics has become louder, brasher, and more annoying than ever. This political climate may mean that it’s easier for less exciting, but still dangerous, programs to slip through the cracks of the American news cycle, and not receive the concern that they deserve. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology professor Guy Reeves and his colleagues are worried they may have discovered one such program.

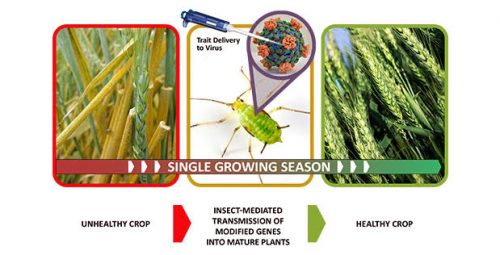

In October 2016, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) announced the Insect Allies Program (IAP). As is typical for DARPA programs, IAP aims to be not a step, but a leap forward in science. This program aims to repurpose insects—instead of being notorious crop killers, it may be possible to use them as tools to spread helpful genes to plants. This program builds off the hypothesis that insects can be controlled to inject viruses into plants, altering their genetic code. This would be accomplished through Horizontal Environmental Genetic Altering Agents (HEGAA).

In the past, if farmers wanted a specific trait in their crops or livestock, they would use artificial selection. Through vertical inheritance of genes, an organism would receive chromosomes from their mother and father. The organisms with the trait most similar to that which is desired would be selected and bred, and the process would repeat. Through artificial selection, it’s possible that the desired effect could be achieved after a few generations; however, it often takes much longer. In contrast, the horizontal transfer used by HEGAAs acts similarly to an infection—instead of waiting for genes to arise by artificial selection, genetic material is injected into the organism, instantly becoming part of its genetic code. The IAP aims to utilize insects to distribute helpful genes to plants. Through this program, these insects would feed on a plant that contains a virus with a desired gene contained within, fly into the field, and infect plants with this gene.

On a molecular level, this technique utilizes CRISPR, a recently developed gene-editing technology. CRISPR works by seeking out specific areas of an organism’s genetic code known as target sequences, cutting them out with an enzyme, and replacing them with a desired sequence. When the insect injects the virus containing the desired gene into the plant, the gene seeks out the target sequences in the plant’s chromosomes and cuts them out. These newly created gaps have to be replaced with new genes. To fix them, CRISPR uses a process called recombination. However, CRISPR can also randomly insert nucleosomes into the plants genetic code, using a different but related process called nonhomologous end-joining. Because the nucleosomes are entirely random, unknown consequences can arise, most of which lead to the plant’s death.

“It’s always much easier to develop a biological weapon than an agricultural help,” Dr. Reeves said. “The random-joining mechanism is at least a thousand times more efficient,” meaning that DARPA may unintentionally develop the technology to fuel a bioweapon. DARPA has stated that they are developing this technology using a pathway that prevents this outcome, but they have not explained what this path is or how they’re following it. The established conventions of science require rigorous reporting on methods and conclusions from any scientific paper, so if DARPA and the universities associated with this project do not follow this path, then it is entirely possible that there could be a paper published that gives a method to create what is effectively a bioweapon: insects that, when released, can kill a whole field of crops. This possible threat concerns Dr. Reeves, especially coupled with the fact that not many people, both in and outside the scientific community, are aware of the program. “That’s the reason, very reluctantly, I decided to write this article,” he said. But he’s still worried that not enough people will hear him.

Despite all the secrecy surrounding the program, Dr. Reeves remains optimistic. After all, the governing body that has prohibited the proliferation of bioweapons since its establishment, the Bioweapons Convention, was founded by the United States under Nixon. Since the convention does not have any military power, not developing bioweapons has existed as a common agreement, based on the morality of each nation’s government. Dr. Reeves is hopeful that the rules set by the Bioweapons Convention are followed, and that the program will indeed help farmers. But in the end, all we can do is wait and see how DARPA manages the risk of publishing the research.