Image Courtesy of “A candidate runaway supermassive black hole identified by shocks and star formation in its wake”

Black holes have long been the source of both advances in astronomy and advances in our understanding of the laws of physics that govern our universe. Supermassive black holes are a specific type of black hole defined by their astounding weights of millions—even billions—of solar masses. Until now, no such supermassive black holes have been found entirely outside of a galaxy, but researchers believe they may have found the first evidence to suggest the presence of a black hole of this nature—one kicked out of its galaxy.

In the aftermath of a galactic collision, the black holes of each former galaxy slowly and steadily spiral toward each other, waiting to merge into an even larger black hole. However, if another galactic collision hurtles a third black hole into the orbiting pair, the impact may destabilize their orbits, ejecting one or more of the black holes from the galaxy. For decades, astrophysicists have predicted the existence of supermassive ejections, but their models have lacked direct evidence, until now.

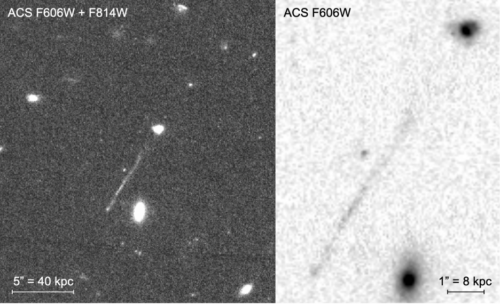

Professor Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University studies stellar populations. While studying dark matter in distant galaxies, he happened upon an intriguing image captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Upon further inspection, he noticed a single unique-looking streak in the image captured by the Hubble Space Telescope—”something I had never seen before,” van Dokkum said. Further investigations of the streak, including spectroscopy with Keck Observatory, could reveal that this streak may be caused by a supermassive black hole escaping its host galaxy. If proven, it will be the first recorded evidence of its kind.

This is a groundbreaking discovery for many reasons. For one, scientists have proposed strong hypotheses surrounding the behavior of these supermassive collisions since 1970, and this evidence would be able to verify fifty years’ worth of research. Further, this discovery makes way for the continued search for evidence to improve our statistical modeling. In particular, van Dokkum is interested in what this discovery could reveal about the formation of supermassive black holes and how one behaves when it is isolated from the center of a galaxy.

“The hope is to find more in the future, that this is indeed a first of many,” van Dokkum said. “Ultimately, the way forward is to find tens or hundreds of these.” He believes that the real potential here is in finding as many examples of this phenomenon as possible so that researchers can better understand the role black holes play in the universe.

The next step for van Dokkum and his team is to confirm their findings with more data. They have already been granted time on the Hubble Space Telescope to conduct further investigations of nuances in this system. Even further down the line, researchers are excited to make use of the 2037 launch of the LISA satellite for the next major discoveries in the detection of supermassive black holes and their mergers.