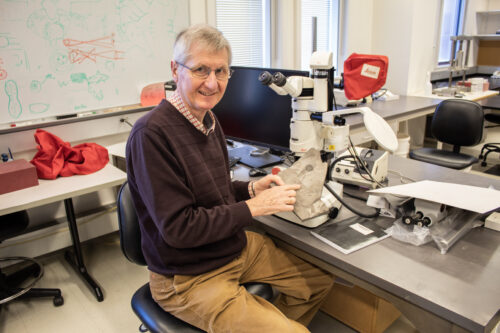

Photo Courtesy of Paul-Alexander Lejas.

Imagine walking into your friend’s house and finding that it’s filled with fossils. Well, that’s exactly what Derek Briggs, a professor of earth and planetary sciences and curator of invertebrate fossils at the Yale Peabody Museum, encountered during his first visit to Samuel J. Ciurca, Jr.’s house some twenty years ago. “His entire house was full of eurypterids, such that there was hardly anywhere to sit down, which was amazing,” Briggs said. Ciurca was a chemist with Kodak in Rochester, New York, and a dedicated fossil collector who specialized in eurypterids, which are commonly known as sea scorpions. One of Ciurca’s most prominent discoveries was a mysterious fossil he nicknamed Ezekiel’s Wheel. Ciurca discovered this fossil alongside eurypterids in a quarry in southern Ontario. Despite his experience, neither he nor others could figure out which genus or species Ezekiel’s Wheel belonged to. As a result of interactions with Briggs and his group, many thousands of Ciurca’s fossils ended up at the Yale Peabody Museum and have been studied by Yale students. One of those students, Nicolás Mongiardino Koch GSAS ’21, worked with Briggs to resolve the nature of Ezekiel’s Wheel. Their success illustrates the importance of working with gifted fossil collectors to acquire important material for advancing science.

Even though Ciurca was not a professional paleontologist, his approach to fossil collecting was scientific in the way that he kept careful notes of the fossils and localities he visited. His paleontological exploits focused on western New York and southern Ontario, Canada, where a sequence of Silurian rocks called the Bertie Group is located. The Silurian period is a geologic period of the Paleozoic Era that occurred more than four hundred million years ago. Ciurca amassed extensive collections from the Bertie Group and became an authority in these rocks and the fossils they contain. In the early 2000s, Yale acquired a large number of specimens from Ciurca, amounting to over ten thousand eurypterids. However, within this collection was the unusual specimen that Ciurca called Ezekiel’s Wheel. “The fossil itself consists of radiating layers of tubes, and it vaguely looks like a wheel,” Briggs said. The wheel-like shape fascinated Ciurca, and he wrote on the slab with the most preserved version of the specimen: “the most beautiful fossil ever found.”

Briggs taught a course titled “Extraordinary Glimpses of Past Life,” where students studied the processes involved in preserving exceptional fossils and completed a research project as part of the assessment. In 2015, Mongiardino Koch was given specimens of Ezekiel’s Wheel for his project and made important progress in interpreting its identity.

Ciurca continued to add fossils to his collection until he died in 2021. In the meantime, Yale placed Ciurca’s fossils on temporary display at the Peabody Museum, and Briggs and his group wrote several papers with him. Upon his death, Ciurca bequeathed many additional fossils to Yale, including new examples of Ezekiel’s Wheel. With this collection, Briggs and Mongiardino Koch were finally able to solve the mystery. A combination of careful study of the anatomy and microstructure of the fossils and an analysis of its relationships with other fossil species—also known as phylogeny—showed that Ezekiel’s Wheel is related to a group of tiny pseudocolonial animals called cephalodiscids. Today, cephalodiscids are attached to rocks on the seabed. Ezekiel’s Wheel, however, is unique among cephalodiscids because it has a large float supporting a series of radiating tubes, each of which houses a tiny organism. “We increased the known range of form of cephalodiscids, living and fossil, and added to the number of known fossils in the Bertie Group associated with eurypterids,” Briggs said. The information reveals a new kind of organization that existed 420 million years ago in the history of marine life.

All in all, the identification of Ciurca’s Ezekiel’s Wheel is one example of how fossil collectors can make an impact on paleontology and evolutionary biology. Fossils that are difficult to interpret may spend some time sitting in museum drawers, but new specimens and methods will eventually reveal their secrets and add to our knowledge of the history of life on our planet.