If one were to peek into Yale’s science classrooms, it is unlikely that he or she would report any gender disparities. In class, there appear to be an equal number of male and female students, and both genders seem to engage equally during lecture. One would assume that scientists, who are trained to think objectively, are completely immune to gender discrimination. However, a recent Yale study by Corinne Moss-Racusin and colleagues suggests otherwise.

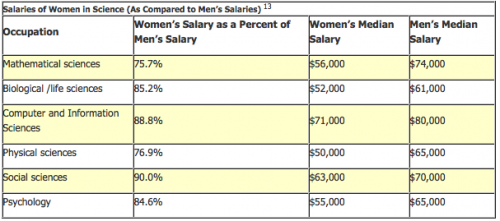

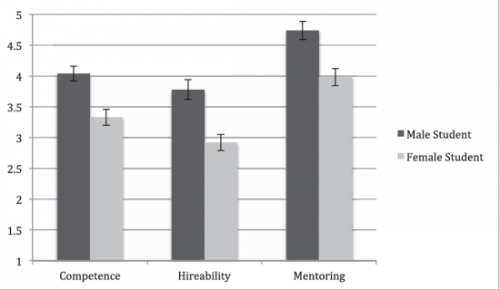

The researchers created a fictional student and sent out the student’s application to science professors at top, research-intensive universities in the United States. The professors were asked to evaluate how competent this student was, how likely they would be to hire the student, how much they would pay this student, and how willing they would be to mentor the student. All of the applications sent out were identical, except for the fact that half were for a male applicant, John, and half were for a female applicant, Jennifer. Results showed that, with statistical significance, both male and female faculty at these institutions were biased towards male students over female students.

Corinne Moss-Racusin, Ph.D, author of a paper on science faculty gender bias and author of this study, states that the motivation to investigate this issue came from the many popular conversations about why gender disparities in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields exist. Some people claim that women are biologically less capable than men in quantitative fields. Other researchers are quick to conclude that women choose to avoid the lifestyle that comes with being a scientist. Both parties assume that gender bias does not exist without actually testing for it in a lab. Therefore, the outcome of Moss-Racussin’s study is shocking.

The implications of this study are alarming, not only for women looking for a professional position in STEM fields, but also for the entire field of science. Moss-Racusin emphasizes the importance of mentoring by stating, “if you look at the paths of successful women, there is one thing they have in common by and large: they all had good mentors.” However, as the study shows, because scientists are less likely to offer women mentorship, the potential contributions of women to science are limited. Meg Urry, Chairwoman of the Department of Physics at Yale, describes the dilemma perfectly: “We have to diversify the profession before it clones itself out of existence.” The only way for science to progress is if we have the broadest and best possible input of brains. However, this progression is impossible unless scientists can find a way of avoiding the gender bias altogether.

Although it may not be possible to completely eliminate gender biases in the immediate future, Moss-Racusin believes that it is possible to reduce their effects by making simple changes in academic departments. Standardizing how often professors meet with students and implementing a third-party check system can ensure that all students are accessing the same levels of support from their academic advisor. Overall, awareness of this gender bias is the only way to keep the playing field level for all Johns and Jennifers.