Staying loyal to a diet is challenging, but keeping track of precisely what you eat while you are dieting may be even harder. Few people have time to stop in the middle of the day to recall exactly how many apple slices they had with breakfast, or how many calories were in the Caesar salad they ate for lunch. Fortunately, these questions may soon be a thing of the past.

A Revealing Molecule

Drs. Brenda Cartmel and Susan Mayne, faculty members in the Epidemiology department at the Yale School of Public Health, collaborated with scientists from the University of Utah in a recent study that establishes a novel way of finding out the amount of fruits and vegetables people have eaten. Their new method relies on measuring the amount of certain type of pigments, called carotenoids, in a person’s skin. Carotenoids give many modern birds and fishes their colors. Beta carotene and alpha carotene, which make carrots yellow-orange, have also been shown to produce a yellow coloring in people’s palms when ingested at high levels.

Humans cannot make their own carotenoids, so we instead get them by eating fruits and vegetables, which are the best sources of these molecules. Because the carotenoids we eat end up as deposits in our tissues, they are prime biological markers of vegetable and fruit intake.

Carotenoids have been a major area of clinical study, but also of mystery. On the one hand, carotenoids seem to be promoters of good health: people who ingest them also have a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. On the other hand, carotenoid supplements have not been found to provide the health benefits that fruits and vegetables offer. It seems that there is something about fruits and vegetables as a whole, not just the carotenoids contained within them, that delivers significant health benefits. Carotenoid supplements – that is, those not eaten as part of fruits or vegetables – have been shown either to have no effect or actually to increase the risk of lung cancer in smokers, at least in the case of the carotenoid beta carotene.

A Novel Approach

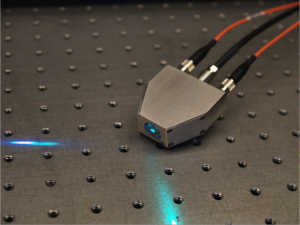

Since carotenoids have the potential to be objective measures of fruit and vegetable intake, scientists have been trying to find reliable and efficient ways of measuring them. Traditionally, carotenoid levels have been measured by taking blood samples and performing chemical analyses, but this procedure is invasive, expensive, and often requires long periods of time to analyze results. The new procedure, which Cartmel and Mayne have developed in conjunction with physicists from the University of Utah, is non-invasive. Whereas blood measurement requires puncturing someone’s skin with a needle, Cartmel and Mayne created a way to measure carotenoid levels by simply placing a beam of laser light on someone’s hand. They used Raman Resonance Spectroscopy, which works by directing a laser beam onto the skin to excite carotenoid molecules. A detector in the instrument registers the signals that these excited molecules emit. In that way, it is able to measure carotenoid levels.

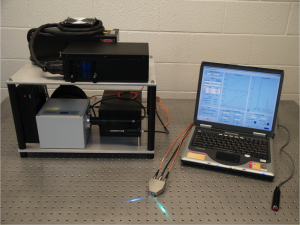

With the help of one of Cartmel’s colleagues, Yale School of Public Health Research Associate Maura Harrigan, I experienced Raman Resonance Spectroscopy myself. I met with Harrigan at the Yale-New Haven Hospital, where the apparatus is housed. I was able to obtain my own carotenoid reading, and perform a reading on her as well. The laser is essentially a bulkier version of the laser pointer you might see your biology professor using during lecture, but we took special precautions and wore safety glasses just to be safe. The laser is linked to a machine, which in turn is linked to a computer that displays the readings.

First, Harrigan handed me a collection of small skin tone plates, and I was allowed to pick the skin color that I thought best matched the color of the underside of my forearm. Next, the bulky area of my palm, which is called the thenar eminence, was cleaned with an alcohol swab. Then the laser was placed on my palm. The machine took it from there and subsequently spat the data onto the computer screen. The whole process took less than a minute.

In collaboration with colleagues from the USDA, Cartmel and Mayne found that their laser scanning method was effective in measuring carotenoid levels and changes in fruit and vegetable intake. To verify their findings, they correlated carotenoid levels with manipulation of fruit and vegetable intake, then compared those results to the results of a conventional blood test. From this comparison the team concluded that skin carotenoids are a reliable indicator of changes in fruit and vegetable consumption.

Moreover, skin carotenoids are likely better than blood carotenoids as a marker of usual fruit and vegetable ingestion. The explanation for this observation is very simple: blood is a transport medium and so changes with daily diet fluctuations. In contrast, skin is a storage medium, so carotenoids found there are more likely to reflect a person’s usual intake.

These results are only the most recent developments among years of research that Cartmel and Mayne have carried out in this area. In 2010, they established that the skin test was as reliable, if not more reliable, an indicator for carotenoid levels as the blood test in the absence of dietary intervention. This laid the groundwork for their 2012 study that showed that a correlation between skin carotenoid levels and fruit and vegetable intake also exists in preschool-age children.

Only the Beginning

From here, Cartmel hopes to test the carotenoid-measuring procedure in various ethnic groups. Her recent study was conducted only on Caucasian subjects. People of other ethnicities differ from Caucasians in the levels of melanin in their skin. Because the test examines pigments in skin, varying levels of melanin could affect the outcomes for non-white people.

In addition to providing both doctors and patients with an improved method of tracking fruit and vegetable intake, the results of this study have much broader implications. In the U.S. healthcare system, an overwhelming amount of attention is given to drugs, disease treatment, and intensive care, while there is far less emphasis on disease prevention, nutrition therapy, and lifestyle medicine. Part of the reason that nutrition therapy has been pushed to the sidelines by the medical establishment is that tracking nutrition and dietary habits is so challenging for both physicians and patients. “We can use this as a method of assessing the success of an intervention. For the most part, people have used self-report, but this is a much more objective measure,” Cartmel says.

Personalized medicine has been emerging as one of the hottest areas in medicine, and Cartmel’s findings will contribute to this field by enabling personalized feedback from doctors. “You could say [to patients], ‘Look, your skin carotenoid levels have increased. You’ve done a great job with your diet.’ It could be a way to provide positive feedback,” Cartmel says.

At the most fundamental level, there is one message that Cartmel says she wants to convey to people after seeing the results of this study: “Eat more vegetables and fruits!” The repeatedly proven health benefits of vegetables and fruits coupled together with this new objective and reliable measure of vegetable and fruit intake have made following a healthy diet easier than ever.

Researchers also now have a foolproof, objective way of finding out what patients are eating or not eating. So watch out: it’s time to eat up or fess up.

About the Author: Kevin Wang is a sophomore in Ezra Stiles prospectively majoring in Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology. He currently serves as Copy Editor for the magazine and has been writing for Yale Scientific since his freshman year.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Dr. Cartmel and Dr. Harrigan for their time, enthusiasm, and generosity.

Further Reading

- Mayne, Susan T., Brenda Cartmel, Stephanie Scarmo, Lisa Jahns, Igor V. Ermakov, and Werner Gellermann. “Resonance Raman spectroscopic evaluation of skin carotenoids as a biomarker of carotenoid status for human studies.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23823930.

- Scarmo, S, V B Duffy, P S Bernstein, W Gellermann, I V Ermakov, H Lin, B Cartmel, H Peracchio, K Henebery, and S T Mayne. “Skin carotenoid status measured by resonance Raman spectroscopy as a biomarker of fruit and vegetable intake in preschool children.” https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22434053.