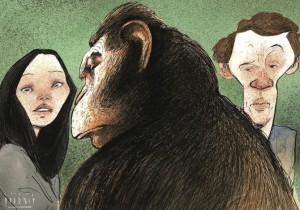

Many of us are familiar with the Planet of the Apes movie series, in which a race of intelligent apes clashes with humans for dominance of the planet. In this series, the apes can speak English, ride horses, and operate machine guns. Uplifted animals — or animals biologically modified to have human intelligence — have appeared in popular science fiction works as intelligent apes, dogs, bears, mice, and more. However, with the development of modern intelligence enhancement technologies, uplifted animals might not be so far from reality, either.

Recent studies show that it is possible to enhance animals’ intelligence by making neurological modifications to their brains. These studies, of course, come with some limitations. For example, endowing an animal with human intelligence would require more than neurological tweaks — scientists would have to alter all aspects of the creature’s biology and physiology in parallel. But research in genetics and neurological disease has started to pave the way for uplifted animals. At the very least, these studies raise important questions in bioethics, questions that should be of interest to experimenters and citizens alike.

Just last year, researchers at MIT discovered a human gene, Foxp2, which appears to be critical in the human capacity for language — our ability to produce and understand speech. The researchers proposed that Foxp2 enables new experiences to be transformed into routine procedures, an essential component of acquiring language skills. When the researchers genetically engineered mice to express Foxp2, these animals learned to run mazes more quickly than their normal counterparts. This finding suggests that the gene helped mice convert experiences into memories. A mouse that knows the twists and turns of the maze will be able to complete it faster. Genetic modifications to animals, some scientists believe, could help prime their brains for speech and language acquisition.

In another study conducted at Wake Forest University in 2012, researchers used rhesus monkeys to study degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. The monkeys given drugs to simulate Alzheimer’s performed predictably worse on intelligence tests than those who were not given the drugs. However, when researchers fitted the diseased monkeys with synthetic neural prosthetics, or brain implants designed to enhance neuron activity, the monkeys quickly regained normal brain function. Then, when researchers implanted the neural prosthetics in normal monkeys, these monkeys scored beyond their original test results. The Wake Forest team concluded that its neural prosthetics could not only restore intelligence to monkeys whose minds had been impaired by disease, but could also uplift normal monkeys by enhancing their mental abilities.

In light of these preliminary findings, the possibility of uplifting animals in the future has caused much speculation and debate. The notion of uplifting animals brings to mind visions of a radical future — perhaps even a future in which chimpanzees talk to humans, cows protest against slaughterhouses, and parrots take math classes. Most likely, we will never have the technology for these visions to come to pass. Nevertheless, these fantasies have sparked concerned conversations about the ethics of uplifting animals.

A handful of philosophers and futurists have put forth a case in favor of uplifting animals. Bioethicist George Dvorsky posits the idea of the uplift imperative — that humans are obligated to cognitively enhance animals if and when such technology becomes available. Dvorsky argues that it would be negligent, unethical even, for humans to purposefully withhold intelligence enhancement technologies from other animals. And other theorists, including science fiction writer David Brin, build upon Dvorsky’s argument by proposing that as the only species to break the “glass ceiling of intelligence,” humans have a moral obligation to help other species.

Conversely, many other bioethicists question whether uplifting animals is scientifically feasible or even desirable. Most animals’ physiologies are not suited for enhanced neural activity or intelligible communication. In practice, comprehensively increasing animals’ intelligence would require impossibly extreme modifications to nearly every aspect of their bodies and minds. Furthermore, as University of Sheffield researcher Paul Raven argues, Dvorsky’s uplift imperative is flawed: This philosophy assumes that human intelligence is the end goal of evolution, which is not necessarily true. Raven also raises the issue of consent, as animals cannot express their agreement to neural enhancement procedures.

Uplifting animals to become as intelligent as humans may be a fantastical scenario, but it is also a scientific possibility that has raised complicated questions. Recent research, such as the studies done at MIT and Wake Forest, reveals that neurological modifications can in fact enhance animals’ intelligence. Still, science has a long way to go before technology will be capable of drastically changing animals’ physical and mental states. In the meantime, the prospect of uplifting animals provokes us to ponder ethical questions, especially as we reexamine our current relationship with other animals. The ability to uplift animals might be mostly science fiction for now, but it is an idea grounded in scientific and cultural realities. Sometimes, these realities are even harder to contemplate than fiction.

Cover Image: Mice that were genetically engineered to express the human gene Foxp2 learned to run a maze faster than their normal counterparts. Image courtesy of BBC.