The human digestive tract is a thriving ecosystem, teeming with life and activity. On an intellectual level, many of us know this, even if it can be discomfiting to think about the trillions of living cells in our guts that constantly work to transmute food into energy. Perhaps more unsettling is an oft-repeated bit of trivia: the bacteria inside of us outnumber our own human cells ten to one. However, new research conducted by Ron Milo, Shai Fuchs, and Ron Sender at the Weizmann Institute of Science has recently proven that this long-standing myth is false, and the ratio is actually closer to 1 to 1.

The 10 to 1 myth originated from a 1972 approximation by microbiologist Thomas Luckey, who used rough estimates on the make-up of human intestines to determine the ratio. He calculated that one gram of intestinal matter contained 100 billion microbes and assumed that an average human had 1000 grams of intestinal matter. Using these numbers, he estimated that 100 trillion microbes thrive in the human body. Luckey cited no evidence for his data—and probably did not anticipate how often it would be cited—but in 1976, scientists further publicized his estimate by comparing it to the approximated 10 trillion cells in the human body, creating the ten to one ratio students are now taught today.

Milo’s team revisited the available literature in order to revise the current estimate. “We share a fascination with numbers in biology,” said Milo. “We believe that getting the numbers right provides a profound understanding of the system one is trying to study.” Looking at some of the quantitative assumptions we make about our body allows us to better characterize its functions and capabilities.

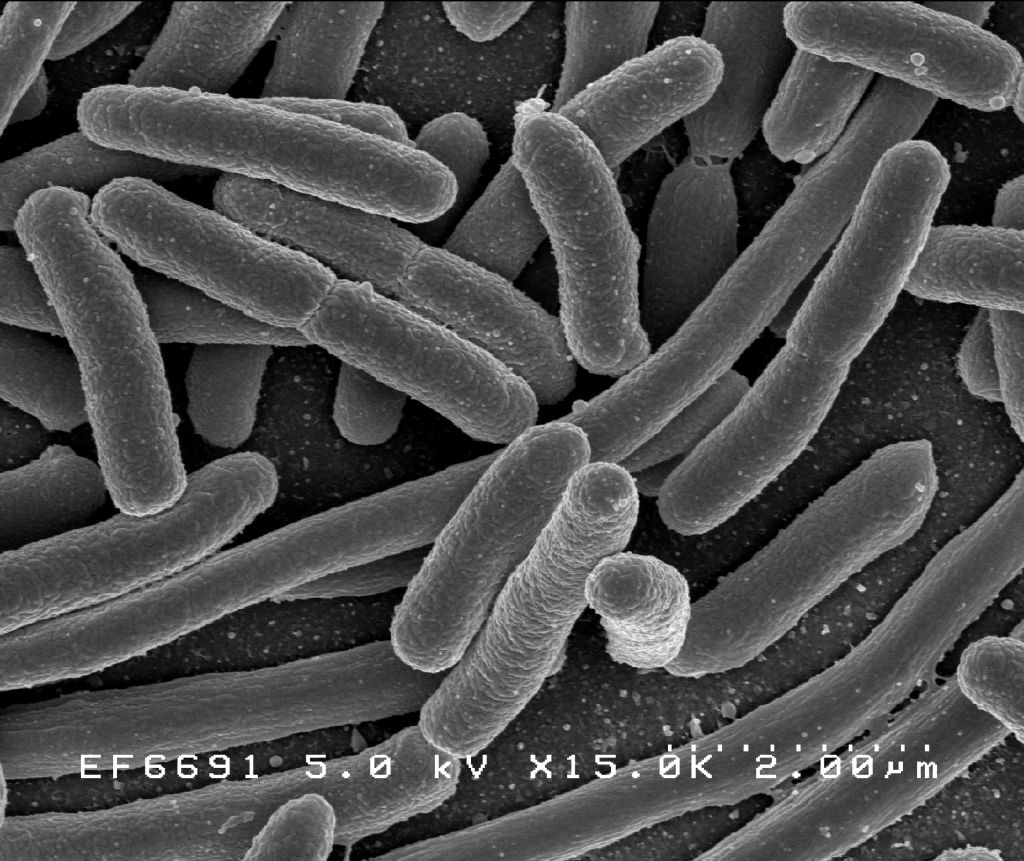

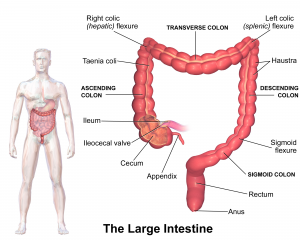

In reviewing the methodologies previously used by researchers, the team found a major error in Luckey’s 1972 calculation: he overestimated the number of bacteria present in the gut by falsely assuming that bacteria reside throughout the entire alimentary canal. In reality, bacteria reside primarily in the colon to assist in its numerous digestive functions. After adjusting for this fact, Milo and his team altered the previous estimate from 1014 bacterial cells to approximately 4×1013 bacteria within our bodies. Milo also calculated an increased number of total human cells, resulting in a revised ratio of approximately one to one.

As with most biomedical estimates, Milo’s calculations rely on a reference human body but do, nevertheless, account for variations between people of different sizes and genders. For example, total blood volume is lower in females than in males—as is the red blood cell concentration—and both factors affect bacteria count. Milo’s team repeated their calculations for women and infants, also taking into account factors such as obesity. The obtained values were within two fold of the standard 1.3:1 ratio.

Regardless, these minute differences between individuals do not detract from the implications of Milo’s study. These new findings drastically differ from the previously commonly accepted ratio. In fact, Milo claims that his newly developed ratio is so close to one, that it could be reversed by a single defecation, causing human cells to outnumber bacterial cells for several hours. Such variation may also occur due to routine medical procedures affecting the colon, a possibility that was not explored with the previously erroneous 10 to 1 hypothesis.

It is important to note that the reduced estimate does not diminish the established biological importance of microbes in our bodies. In fact, it might help researchers look beyond cell count number. “I think it will help focus the motivation of microbiome studies on the many great reasons for studying [bacteria’s] effects,” said Milo. Bacteria play crucial roles in immune system regulation, food digestion, and nutrient production. It is also likely that bacteria employ more genes and produce a wider range of chemicals than our own cells in ways that are beneficial to our system.

Nevertheless, these improved approximations highlight the inevitable possibility of error in scientific calculations and pave the way for further investigations of the human microbiome. For example, most of our assumptions about bacteria in the gut stem from the analysis of bacteria found in feces. However, Milo questions how different the density of internal bacteria might be. “This is just one example of an open question that is highlighted now because we want to get the best quantitative answer,” he said. Investigations into this and other quantitative problems, such as the number of viruses found in the human body or the number of synapses in the brain, may place into question many facts about our species currently taken for granted.

More information on how numerical methods can answer biological questions can be found freely in the ebook Cell Biology by the Numbers by Milo and his colleague Rob Phillips, professor of biophysics and biology at Caltech.