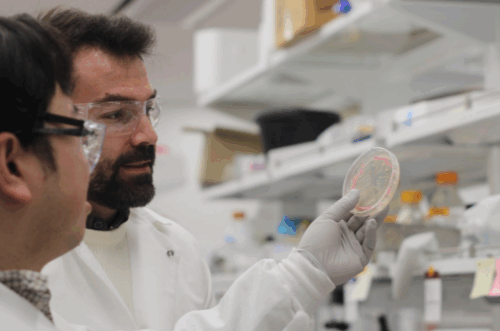

Art by Alondra Moreno Santana. Photography by Michelle So.

Surprisingly, the strongest organisms in the world are made up of only one cell. These are bacteria. While they can’t do much on their own, they are powerful in numbers. Bacterial communities with enough members are capable of forming vast three-dimensional structures called biofilms. These biofilms can be found in every environment on Earth, from frozen arctic glaciers to the scalding-hot waters of geysers. They even form naturally within the human body, helping us digest food and supporting the development of babies’ immune systems.

However, other bacterial biofilms are less friendly. Strep throat, urinary tract infections, cholera, tuberculosis, and a slew of other diseases are caused by foreign bacteria forming biofilms within the body, disrupting our natural physiology with consequences that range from inconvenient to deadly. But these biofilms may have fatal flaws—potential self-destruct mechanisms that regulate how the bacteria assemble and disperse. Currently, a team led by Yale researchers is investigating these powerful bacterial on-off switches, gaining new insights into biofilm behavior and opening the door to potential treatments for a wide range of bacterial diseases.

Getting to this point has not been easy. The study of biofilms formed by harmful, foreign bacteria has long lagged behind research into their friendly counterparts, especially in understanding how these structures form and break apart. One of the biggest challenges lies in understanding the material that holds these biofilms together. The structural glue is made up of complex sugars—or more formally, polysaccharides—that bacteria secrete into their environment to form a sticky, protective matrix. While human cells are also supported by a network of secreted proteins and sugars called the extracellular matrix (ECM), there is no homology, or one-to-one correspondence, between the components of the human ECM and bacterial biofilms. The problem is compounded by the huge diversity of sugars in bacterial biofilms, including some that do not have equivalents created by the human body.

Despite these obstacles, Jing Yan, an assistant professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology at Yale University, and his postdoctoral associate Alexis Moreau were undeterred. Together with their team, they used an ingenious workaround to study the formation and dispersal of bacterial biofilms, offering new insights into these complex microbial communities.

Seeing what Sticks

Yan and Moreau chose to study the biofilms formed by Vibrio cholerae (Vc) as their model organism. As its name implies, Vc is responsible for cholera, a highly virulent disease that spreads through contaminated water and kills tens of thousands of individuals each year. “Vc is a very important pathogen. Whenever there is a disruption in the purified water, in the access to the purified water purification system, then there could be a potential outbreak. [You] never know what will happen next,” Yan said. But Vc is not just interesting because of its lethal consequences—it is also easy to manipulate genetically. Yan and Moreau were able to take advantage of this fact, suppressing or “knocking out” certain Vc genes in order to see their effects on the biofilm.

The first culprit the team investigated was Vibrio polysaccharide (VPS), the main sugar in the biofilms formed by Vc. VPS is the primary structural component of Vc biofilms, serving as a scaffold for a number of proteins that are integral to the adhesion of the biofilm. For decades, scientists had thought VPS itself acted like an adhesive, attracting nearby cells in the biofilm and promoting a process called bridging aggregation, where cells stick together in loose, disorganized clumps. The theory was that the more sugar was added, the stronger the attraction the cells would feel, creating even larger aggregates. In order to investigate this hypothesis, the team took a strain of Vc and knocked out the genes responsible for all of its major matrix proteins, controlling for all their effects, and placed the bacteria into different kinds of media. When they tried VPS, they saw that the cells did not clump in disorganized groups as predicted. Rather, they assembled into a tight, parallel arrangement, which filled the space extremely efficiently.

So, if Vc biofilms aren’t held together by bridging, what keeps them from falling apart? It turns out that the structures that the Vc cells formed in Yan and Moreau’s experiment, called parallel linear aggregates, are the telltale signs of another adhesion mechanism called depletion-attraction. Unlike gravity or the electrostatic interaction between positive and negative charges, depletion-attraction is not a direct force. Rather, it emerges from the principle that systems tend towards maximum disorder, or entropy. Imagine a few Vc cells suspended in a sea of small VPS particles. When two cells come close enough together, the VPS particles can no longer enter the gap between them, creating a “depletion zone.” This exclusion actually increases the order of the system by restricting where the particles can go. To restore disorder, the system responds by pushing the cells together, eliminating the depletion zone and freeing up the VPS particles to traverse a larger area.

Attraction and Depletion

But does depletion-attraction account for the behavior of the biofilm throughout the entire growth process? To test this question, the researchers examined aggregates at different points of their growth. They found that early in biofilm development, cells secreted VPS and also were coated with VPS, enabling cells to be anchored to the ECM via sugar-sugar interactions. However, after a sufficient cell density had been reached, cells were no longer coated with VPS, unmasking repulsive cell surface-VPS interactions and triggering depletion-attraction. This process was accelerated by treating the cells with the RbmB, a protein that cleaves sugars off protein anchors by causing surface modeling and creating cells with VPS-free coats.

On the other hand, treating VPS-coated cells with the cell-matrix adhesion proteins Bap1 and RbmC accelerates bridging aggregation. Although previous studies have shown that Bap1 is necessary for helping biofilms adhere to other surfaces, such as the inner lining of the gut, they have never elucidated how the protein interacts with ECM sugars like VPS to mediate this adherence. “The biofilm is made together because you have this complex matrix, the combined matrix of polysaccharide[s] and proteins that are not independent. They interact with each other. This interaction is what we’re really interested in seeing,” Yan said.

The team found that treating VPS-coated cells with Bap1 in the early growth phase, without the presence of additional secreted VPS, created loose, disorganized aggregate patterns characteristic of the bridging aggregation model. Moreover, when extracellular VPS was present alongside Bap1, the cells strongly adhered to the ECM, indicating a cooperative interaction between the protein and the polysaccharide in driving biofilm assembly.

The Aggregation Switch

Yan and Moreau developed a model of biofilm growth that explained how bacterial communities switch between different modes of aggregation. In early growth phases, when there are abundant nutrients for all the bacterial cells in a community, the cells are coated with VPS. During this stage, the presence of Bap1 and RbmC facilitates bridging aggregation, allowing cells to connect through shared interactions with the ECM. As nutrients run low, however, the system shifts: RbmB activity cleaves the VPS coats off cells, and the cell-matrix interaction switches from attractive to repulsive, triggering a transition to dispersion aggregation. Interestingly, the model switch requires nearly all the VPS coats to disappear, meaning the bridging aggregation mechanism usually dominates over the dispersion mechanism throughout most of biofilm development. This likely explains why biofilms tend to grow steadily until a critical point, after which cells begin dispersing from the community.

In this model, the aggregation mode switch seems to underlie the activation of biofilm dispersal. In fact, in the absence of a VPS coat, dispersion-aggregated cells are no longer held within the matrix and slough off the biofilm. Therefore, surface remodeling catalyzed by RbmB, or simply by depleting VPS sugar levels, causes the cell-matrix interaction to become repulsive, the linchpin for biofilm dispersal. “If you just apply a small flow [of RbmB] right on those aggregates, those bacterial cells aggregated to each other are just simply eliminated by the flow. There are some implications [that this] could be a potentially useful strategy,” Moreau said.

This research opens exciting possibilities for controlling harmful bacterial biofilms by manipulating how cells interact with their matrix. By targeting the switch from attraction to repulsion, one can imagine the development of therapies that trigger biofilm dispersal on demand. This approach holds promise not only for treating persistent infections but also for manipulating biofilms to treat disruptions in bacterial communities underlying disease. Understanding and harnessing these cellular dynamics could mark a major shift in how we manage bacterial communities in both medicine and beyond.